SignificanceThe rapid development of 5G, cloud-based service, artificial intelligence, and the Internet of Things has led to explosive growth in data communication traffic, resulting in a dramatic increase in energy demand. To meet this ever-growing demand, energy-efficient optical transmission systems are required to support high-speed optical links. The key component of such systems, ranging from long-reach applications to short-reach interconnects in data centers and on-chip optical interconnects, is the electro-optical (EO) modulator. In this regard, EO modulators have continuously been the focus of research in this field since the emergence of optical communications. Given the challenges posed by data traffic and the energy crisis, it is imperative to develop high-performance EO modulators to support high-speed data transmission with low-power consumption, targeting several femtojoules per bit for next-generation transceivers. EO modulators can convert signals from the electrical domain to the optical domain at high speed. The amplitude, phase, frequency, and polarization of the optical carrier can be exploited to encode information. EO modulators are categorized into free-space and integrated types. In the former category, optical waves propagate freely, and free-space modulators can be based on multi-layers, metasurfaces, and diffraction grating structures. In contrast, integrated modulators in the latter category utilize guided modes within photonic integrated circuits. In this review, we exclusively focus on the integrated EO modulation. In recent decades, various EO modulators integrated on different photonic integrated circuits have been extensively studied, including silicon, indium phosphide (InP), and silicon-organic hybrid (SOH) structures. Pure silicon-based modulators operate through carrier injection or depletion within p-n junctions integrated into optical waveguides, which leads to an inherent trade-off between modulation efficiency and optical loss. InP-based modulators, while capable of achieving high data transmission rates, are constrained by intrinsic modulation nonlinearity, substantial optical loss, and high costs, thus limiting their widespread application. SOH modulators leverage the ultra-high EO coefficient of engineered polymers, yet they often suffer from considerable optical loss and susceptibility to temperature variations. Lithium niobate (LN) is a ferroelectric crystal prized for its linear Pockels effect, broad transparency across wavelengths, and stable physical and chemical properties. Over recent decades, LN has stood out as a highly promising material for photonic devices. Notably, its linear EO effect (r33≈33 pm/V) has enabled the development and commercial availability of high-speed LN EO modulators, crucial for long-distance telecommunications systems. More recently, thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN) has emerged as a topic of extensive interest. Unlike conventional LN waveguides, TFLN waveguides exploit high refractive-index contrast to tightly confine optical and electric fields, thereby supporting compact footprints and optimizing EO modulation efficiency. In this review, we mainly concentrate on the TFLN-based EO modulators and their applications.ProgressTFLN-based EO modulators, which offer advantages such as a small footprint, high bandwidth, and low power consumption, could outperform counterparts based on bulk LN crystal, making them highly competitive in optical communications. In the first section (Sec. 1) of this review, we briefly describe current bottlenecks in optical communication systems and introduce EO modulators across various integrated photonic platforms. To better understand LN crystal materials’ characteristics, we summarize their development history and manufacturing processes (Fig. 2) in Sec. 2, which covers both LN crystal and TFLN-based wafers. The subsequent focus is on recently demonstrated TFLN-based modulators with various structures, including non-resonator types (Fig. 5), resonator types (Fig. 9), and others (Fig. 12). Moreover, various heterogeneous integration technologies of TFLN with other material platforms are summarized in detail, such as die-to-wafer bonding (Fig. 13), rib-loaded waveguides, and micro-transfer-printing (Fig. 14). The end of Sec. 3 describes the TFLN-based EO modulators designed for multi-channel operation (Fig. 16) and diverse operating wavelengths (Fig. 15). Modulation performances of different EO modulator types are comprehensively compared and evaluated in Tables 1 to 4. Finally, Sec. 4 discusses applications of TFLN-based modulators, including EO comb generation, tunable and mode-locked lasers, EO isolators, microwave processing engines, and EO programmable optical switches.Conclusions and ProspectsTFLN has emerged as the leading EO integration platform in recent years. TFLN-based modulators boast ultrahigh speed and ultralow power consumption, poised to noticeably influence optical communications, microwave photonics, and quantum information applications. Beyond its linear EO effect, TFLN also exhibits acousto-optical, second-order nonlinear, piezoelectric, and pyroelectric properties. Recent advancements have showcased a range of high-performance devices such as periodically poled LN, acousto-optical modulators, and surface acoustic wave filters. Thus, TFLN is expected to drive rapid progress in optical communication, computing, sensing, and other photonic information processing fields.

SignificanceWith the advent of big data and artificial intelligence eras, key enabling technologies such as high-capacity optical communication, high-performance computing, and high-sensitivity sensing and detection have experienced rapid development. Photonic integrated systems have attracted increasing attention, elevating demands on both the performance of basic building blocks and the overall integration and scalability of the system. Optical waveguides, fundamental units of optical interconnects in photonic integrated systems, offer notable advantages over traditional electrical wires, including higher data capacity, lower loss, and improved resistance to electromagnetic interference. Traditional optical waveguide structures are primarily fabricated using two-dimensional (2D) semiconductor fabrication processes, constraining light propagation to a single plane. Given that basic photonic building blocks face diffraction limits, achieving device miniaturization through advanced fabrication technology nodes, unlike those in microelectronics, is challenging. Therefore, the number of integrated devices on a single chip is limited by the chip’s footprint. To overcome these constraints of traditional 2D integration technology, there is an escalating need for three-dimensional (3D) integration techniques, which promise superior performance and increased integration density.The silicon photonic platform, compatible with complementary metal oxide semiconductor processes, is vital for photonic integrated devices. Currently, various photonic devices have been realized on the silicon-on-insulator platform, encompassing low-loss optical waveguides, passive optical waveguide devices, high-speed modulators, and detectors. As integrated systems become more complex, routing waveguides on a single device layer becomes more challenging. Efficient interlayer coupler structures capable of routing the light into another device layer facilitate waveguide routing in 3D stacked photonic structures. These interlayer couplers not only enable vertical light transmission between different device layers but also substantially reduce waveguide crossings, associated crosstalk and loss. This method of 3D photonic integration enhances intensity density and system scalability.Beyond integrating different silicon-based materials like silicon, silicon nitride, and silicon oxide waveguides, silicon-based materials can be combined with other heterogeneous materials exhibiting superior electro-optical and light-emitting properties, such as thin-film lithium niobate (TFLN), Ⅲ-V group materials, and various two-dimensional materials. By leveraging the exceptional optical or electrical properties of these diverse materials, the performance of individual optical chips is significantly improved. Moreover, the 3D stacking of optical chips and electrical chips via advanced packaging techniques achieves photonic-electronic convergence, improving bandwidth and power consumption.Femtosecond laser direct writing (FLDW) technology plays a crucial role in manufacturing photonic-integrated devices. This technology harnesses the ultra-short duration and high peak power of femtosecond laser pulses to make precise modifications in transparent dielectric materials. FLDW’s key advantage lies in its ability to accurately control refractive index changes in optical waveguides, facilitating low-loss optical transmission while preserving high mechanical strength and chemical stability. These attributes make FLDW essential in modern optical communication systems and extended transmission distances. Compared to traditional optical waveguide fabrication methods, FLDW offers a more flexible and controllable 3D processing approach. It allows for the direct writing of intricate photonic structures on various material platforms, including glass, crystals, and polymers, broadening application opportunities in fields like optical communications and signal processing.ProgressWe focus on two main types of multi-material system 3D integrated optical waveguide technologies: 3D stacking technology and femtosecond laser fabrication technology. Firstly, we introduce 3D optical coupling technology based on interlayer couplers and 3D integrated optical waveguide devices. In 3D integrated optical waveguides, the interlayer coupler is the key component connecting different device layers and significantly affects the system loss. Light transmitted in one waveguide layer couples to another layer through these interlayer couplers, enabling optical path switching within the 3D structures. Depending on their material applications, interlayer couplers are categorized into silicon/silicon nitride interlayer couplers and silicon-based heterogeneous integrated interlayer couplers. We then discuss photonic-electronic co-integrated devices based on 3D stacking technology. Early data communication systems using discrete photon-integrated chips and electrical control modules have limited performance in terms of energy efficiency, bandwidth, and latency. To enhance optical module performance, efforts have been focused not only on developing 3D integration technology for passive optical waveguide devices but also on heterogeneous integration schemes for devices and corresponding electrical control modules in active optical chips. These schemes are mainly classified into four categories: monolithic integration, 2D integration, 2.5D integration, and 3D integration. Currently, 2.5D and 3D integrated technologies are applied in high-performance optical transmitters, receivers, wavelength-division multiplexing transceivers, and optical interconnect modules. We further explore 3D integrated optical waveguide devices based on FLDW technology. Passive devices, such as polarization multiplexing devices, mode multiplexing devices, and fan-in/fan-out devices, play crucial roles in optical communication systems. Polarization multiplexing devices utilize the birefringence effect of waveguides to multiplex and demultiplex optical signals of different polarization states, thereby increasing system transmission capacity. Mode multiplexing devices enhance communication capacity by multiplexing signals of different spatial modes in multimode optical fibers. Fan-in and fan-out devices address the efficient coupling between multi-core fibers and single-mode fibers or photonic integrated circuits, facilitating the construction of high-density integrated optoelectronic systems. Additionally, topological quantum devices based on FLDW are widely used to explore interactions between topological effects and particle interactions in depth.Conclusions and ProspectsOverall, compared to existing optoelectronic integrated devices, 3D integrated waveguide devices based on multi-material system can significantly enhance integration levels by leveraging the expanded space dimension. However, this also increases fabrication and packaging complexity. Future development in multi-material system 3D integrated optical waveguide devices will require a careful trade-off between complexity, system performance, cost, and yield. With ongoing improvements in device design, fabrication processes, and wafer-level testing, these devices hold promising potential in various fields, including high-speed large-capacity optical communications, data center optical interconnects, high-performance optical computing, quantum information processing, and intelligent microsystems.

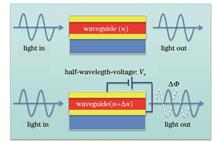

SignificanceThe information industry has profoundly affected people’s lives due to advancements in technologies such as 5G, optical computing, the internet, sensing technologies, artificial intelligence, and multimedia/data/signal processing. These innovations have spurred major changes and opportunities within the optoelectronic device industry. One critical challenge is the demand for high-speed communication, which requires the rapid transformation of electronic signals into optical signals.ProgressThe heart of this transformation lies the development of high-performance electro-optical (EO) modulators. These devices translate electrical signals into the optical realm, which facilitates the transmission of high-bandwidth information while minimizing electrical interference. EO modulators are essential in optical communication systems, where they regulate optical signals. As the demand for faster EO signal conversion grows, the requirements for EO modulators become increasingly stringent. Key criteria include: 1) low drive voltage; 2) minimal optical loss; 3) low energy consumption; 4) high bandwidth, among others. EO polymers offer distinct advantages over other materials for modulator fabrication. They can achieve an EO coefficient (r33) exceeding 300 pm/V in neat-film and over 100 pm/V in device. In contrast, commercial lithium niobate, a common modulator material, typically shows lower EO coefficients. The high r33 value of EO polymers indicates their ability to achieve significant modulation with lower voltages, which makes them highly efficient for high-speed applications. Additionally, EO polymers exhibit a low microwave/optical velocity mismatch, which simplifies the design of modulator electrodes for achieving rapid modulation. These characteristics enable EO polymer modulators to operate at frequencies exceeding 100 GHz, ideal for applications requiring rapid data transmission and processing. Moreover, EO polymers can be processed and integrated with various materials and components, including semiconductor light sources, detectors, low-voltage CMOS drivers, and both inorganic and polymeric waveguides. This integration capability enhances the versatility of EO polymer modulators, thus allowing for customized optimization to meet specific application and device configurations. In 2002, Mark Lee and his colleagues demonstrated ultra-high bandwidth modulation ranging from 25 to 145 GHz in EO polymer MZI modulators (Fig. 12). With advancements in materials science, the EO coefficient of EO polymers can exceed 100 pm/V, resulting in a VπL of around 1 V·cm (Fig. 13). Integrating EO polymers with silicon slot waveguides helps foster the development of more compact modulators. Modulation speed of up to 112 Gb/s has been realized using a 1.5 mm long slot waveguide. EO polymers have also been combined with metal plasmonic structures. By filling the polymer into the metal slots, both electric and optical fields can be concentrated within the metal slots, thereby enhancing the EO interaction. Modulators with an effective phase shift length of only 6 μm correspond to Vπ=10 V and a modulation bandwidth of 70 GHz. Additionally, ring resonator modulators with high bandwidth and high EO tunability have been developed.Conclusions and ProspectsBased on advancements in organic molecular science, guided optics, and microwave theory, EO polymer materials, and their modulator structures have made enormous progress over the past decade. In terms of materials, scientists have systematically addressed several challenging issues through innovations in polymer compositions, chromophores, and host materials. These advancements provide a robust material foundation for the practical implementation of related devices and chips. In terms of device development, researchers from Japan, Germany, Switzerland, and China have successively pioneered “cladding-free structures”, “ultra-thin silicon structures”, “silicon-based slot structures”, “metal plasmonic structures”, and “silicon nitride micro-ring structures”. These innovations fully leverage the unique advantages of EO polymers, including high EO coefficients, broad intrinsic bandwidths, and good compatibility with multiple material systems. These breakthroughs have effectively overcome the limitations of traditional modulation techniques in terms of energy consumption and bandwidth.

SignificancePhotonic integrated circuits (PICs) have been extensively researched and applied in optical interconnections, optical communication, and LiDAR. To further expand the scale and performance of photonic chips, three-dimensional (3D) PICs have emerged as a prominent research focus. 3D PICs represent an advanced type of PICs that achieve spatial expansion through coupling or three-dimensional waveguides, allowing light to propagate beyond a two-dimensional plane within the waveguide. Presently, most research and development in 3D PICs is focused on inorganic materials such as silicon, silicon nitride, and high-index silica. The preparation of 3D PICs on these material platforms necessitates polishing processes at the wafer level, which significantly increases fabrication complexity and cost. Among various optical platforms, polymer-based planar lightwave circuits stand out for their flexibility, low power consumption, and high performance. Polymers are cost-effective and can be processed using simple techniques such as spin coating and photolithography. Their fluidity allows for the creation of flat cladding without additional polishing, providing a foundation for multi-layer devices. This fluidity also simplifies hybrid integration with other material platforms. In the field of laser direct writing, many significant works have focused on waveguides based on inorganic materials. While these devices offer clear advantages in terms of propagation loss, they are limited in their capacity for modulation and reconfiguration, which impedes further functional expansion. In recent years, there has been the development of high-performance hybrid integrated photonic devices using unconventional materials such as Ⅲ-V group material, lithium niobate, and lithium tantalate, in conjunction with conventional silicon waveguides. Three-dimensional integration is regarded as the inevitable path to achieving high-performance hybrid integrated photonic devices. The polymer photonic platform presents a flexible and cost-effective alternative for developing 3D hybrid integrated chips, thus expanding future functionalities.ProgressPolymer-based 3D PICs are primarily fabricated using ultrafast laser inscription (ULI) and multi-layer stacking techniques. ULI offers precise machining and flexibility. For instance, Christian Koos’s group introduced the concept of photonic wire bonding (PWB) in 2012, enabling the connection of polymer waveguides with three-dimensional geometries to bridge nanophotonic circuits across different chips (Fig. 1). In 2018, they utilized PWB technology to connect indium phosphide (InP)-based horizontal-cavity surface-emitting lasers to passive silicon photonic circuits, achieving insertion losses as low as 0.4 dB (Fig. 2). PWB technology paves the way for hybrid photonic multi-chip assemblies that integrate known-good dies of different materials into high-performance hybrid multi-chip modules. Meanwhile, researchers at HHI have theoretically investigated and experimentally demonstrated the use of 3D PolyBoard PICs with multiple waveguide layers as a practical solution for realizing two-dimensional optical phased arrays (OPAs) with end-fire waveguides (Fig. 4). Similarly, Min-Cheol Oh’s group has developed a design and fabrication process for 3D hybrid integration OPA using silicon nitride and polymer (Figs. 13 and 14). In our group, we focus on the functional integration of polymers using 3D polymer PIC fabrication technology. We have demonstrated a dual-layer optical encryption fluorescent polymer waveguide chip based on optical pulse-code modulation technique (Fig. 7) and a 3D optical switch with thermo-optical (TO) and electro-optical (EO) tuning effects (Fig. 12). In addition, we also researched on the fabrication technology and design of hybrid integration of organic and inorganic waveguides (Figs. 9 and 10). Polymer-based 3D PICs not only provide an expandable physical dimension but also offer an optical platform compatible with a variety of materials.Conclusions and ProspectsTechniques like ultrafine laser processing, deposition, and lithography enable the preparation of complex 3D PICs. Current efforts focus on scaling up and enhancing functionalities such as phase shifters. Polymers offer potential for achieving gain amplification, optical nonlinearity, and other special properties, warranting further exploration to improve PICs’ comprehensive performance parameters. Despite their advantages, polymers face challenges like temperature and humidity sensitivity, limiting their use in extreme environments. However, progress in addressing these stability issues is ongoing. Continued research and development in polymer materials for photonic platform, particularly in 3D configurations, promise advancements not only in traditional optical communication and optical interconnect but also in quantum and space optics, leveraging processing and performance characteristics.

SignificanceThe world is experiencing an unprecedented information explosion. The rapid development of high-performance computing (HPC), the Internet of Things (IoT), and artificial intelligence (AI) has introduced new demands for transmission bandwidth and information capacity. However, the bottleneck of integrated circuits is gradually emerging with the slowdown of Moore’s law. Compared with traditional integrated electric circuits, photonic circuits stand out due to their unique advantages such as low power consumption, high operating speed, and multi-lane processing capability. They are regarded as a key technology in the “post-Moore era.” Photonic integrated circuits (PICs), utilizing photons as the information carrier, have emerged as a crucial technology to overcome the communication capacity crunch in modern information society. High-quality optical materials and advanced integration strategies are essential cornerstones for photonic circuits. Silicon, as a dominant semiconductor material, is a popular photonic platform owing to its large refractive index and good compatibility with the CMOS processing procedure. However, silicon exhibits a relatively high propagation loss in the communication band and strong two-photon absorption (TPA) and free-carrier absorption (FCA) effects, hindering its further applications in large-scale integrated circuits and nonlinear photonics. In recent years, a variety of alternative materials have emerged, including silicon nitride, thin film lithium niobate (TFLN), aluminum nitride, silicon carbide, and chalcogenide glasses (ChGs). Key parameters of common photonic materials are summarized in Table 1. It can be seen that the refractive index of the ChGs can be flexibly tuned over a broad range. In addition, ChGs have been extensively used in optical signal processing due to their considerable photoelastic coefficients, low propagation loss, broad transparency window, and good compatibility with various material platforms. Achieving multifunctional PICs on a single chip has become a hotspot for researchers. However, no single material can fulfill all the requirements ranging from signal generation, modulation, transmission, to detection. Therefore, heterogeneous integration is considered the optimal approach for the future evolution of integrated photonics.Progress In this paper, we review three applications of heterogeneous chalcogenide photonics based on the “ChGs+X” material platform: high-efficiency acousto-optic modulation, on-chip nonlinear parametric frequency conversion, and rare-earth ion-doped waveguide amplification (Fig. 1).1) Acousto-optical modulation: Current commercial acousto-optic modulators (AOMs) are typically made from bulk piezoelectric crystal materials like tellurium dioxide (TeO2) or lithium niobate, but their high power consumption and large volume limit their application in photonic circuits. With the rapid development of “ion cut” technology and the success of TFLN, on-chip acousto-optic modulators based on TFLN have been reported in recent years (Fig. 2). However, dry etching lithium niobate smoothly is challenging due to its chemical inertness. In addition, isolating the TFLN from the bottom SiO2 substrate is difficult due to its fragility. To address these issues, heterogenous waveguide structures are designed to achieve high-efficiency on-chip AOMs by utilizing the soft chalcogenide waveguide loaded on the low-loss TFLN. This strategy enables the creation of high-efficiency acousto-optic modulators without the need for etching or suspending the TFLN (Figs. 3-4).2) Parametric frequency conversion: The χ(2)-based nonlinear optical effect has been extensively studied. Various material platforms have been proposed to achieve efficient parametric frequency conversion, including lithium niobate, some Ⅲ-Ⅴ materials with intrinsic χ(2) nonlinearity, as well as silicon and silicon nitride with externally induced χ(2) properties. Among them, lithium niobate has been employed to achieve high-efficiency χ(2) nonlinearity by dry etching and periodical domain engineering of lithium niobate. However, this fabrication process is complex and not compatible with the CMOS procedure. Recently, bound states in the continuum (BICs) have been suggested for obtaining second harmonic generation (SHG) via modal phase matching without the need for etching the TFLN. However, the conversion efficiency is low and not suitable for wideband applications. In our work, we propose a heterogeneous integration strategy by integrating chalcogenide strip waveguide with TFLN slab (Fig. 5). This approach has enabled the realization of on-chip high-efficiency SHG and observation of broadband parametric conversion efficiency via the effect of cascaded second-harmonic generation and difference-frequency generation (cSHG-DFG).3) Optical waveguide amplification: Erbium-doped waveguide amplifiers (EDWAs) have become indispensable components in large-scale photonic circuits. To date, different material platforms and fabrication methods have been utilized to obtain efficient EDWAs such as erbium-doped Al2O3 via atomic layer deposition (ALD), erbium-doped TFLN, silicon nitride with erbium ion implantation, and rare-earth-doped chalcogenide films. However, the gain properties of ChGs-based waveguide amplifiers are lackluster for practical applications due to their intrinsically low solubility of rare-earth ions, low luminous efficiency of chalcogenide hosts, and increased etching complexity when introducing erbium ions into chalcogenide films. To address these challenges, we propose an efficient waveguide amplifier prototype without the need to dope the chalcogenide films directly (Fig. 8). The waveguide consists of a low-loss chalcogenide waveguide on a highly-doped erbium-doped Al2O3 thin film. This work facilitates the development of an efficient waveguide amplifier based on integrated chalcogenide photonics.Conclusions and ProspectsIn summary, ChGs have emerged as promising candidates in PICs. Enhancing the functionalities of ChGs by adopting integrated “chalcogenide+X” heterogeneous platforms offers valuable insights for the future development of PICs in various research fields, including optical computing, optical memory, and integrated optical engines.

ObjectiveLithium niobate based integrated photonics has been receiving extensive attention over the past decades, and its development has gained significant momentum recently thanks to the emergence of lithium niobate on insulator (LNOI). While ensuring the high performance of the device, scalable fabrication and fiber compatibility are also particularly important for practical applications. Micrometer waveguides based on 3-μm thick LNOI show excellent integration potential. For example, the lens fiber or high numerical aperture fiber can be directly coupled with the micro-waveguide with high efficiency, and the overall insertion loss of the device is small. The fabrication process of micro-waveguides by UV lithography and plasma dry etching features low fabrication cost and technical difficulty. In addition, the mode area of micro-waveguides is several times smaller than that of conventional proton-exchange or titanium indiffused waveguides, which ensures higher conversion efficiency. Here we propose to design and fabricate the LNOI micro-waveguide on 3-μm thick LNOI, demonstrating its high performance in second harmonic generation (SHG) and sum-frequency generation (SFG) at the optical telecommunication band. The excellent frequency conversion capability, scalable fabrication, and fiber compatibility make the LNOI micro-waveguide highly appealing. We expect it to form a variety of functional devices in the future and promote the development of fundamental physics research and optical quantum information applications based on integrated photonics.MethodsWe fabricate the periodically poled LNOI (PPLNOI) micro-waveguide by direct electric poling followed by UV lithography and plasma dry etching techniques. We adopt the first-order quasi-phase matching (QPM) at 1550 nm, which determines the poling period. A 3-μm z-cut magnesium-doped lithium niobate on insulator (MgO∶LNOI) wafer is patterned via ultraviolet lithography and electron beam evaporation for electrodes. The electrodes are used for direct electric poling to achieve periodic domain reversal, and PPLNOI samples are obtained. Then we use UV lithography and plasma dry etching technology to transfer the designed micro-waveguide pattern to the PPLNOI layer. During the etching process, argon ion bombardment is used, and the etching depth reaches 3 μm to completely penetrate the LNOI layer. Then, a protective layer of silica about 1 μm thick is deposited on the surface by plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). Finally, the end faces of the micro-waveguide are optically polished to obtain a buried PPLNOI micro-waveguide.Results and DiscussionsThe processes of SHG and SFG are tested to evaluate the second-order nonlinear performance of the PPLNOI micro-waveguide. The normalized SHG efficiency of the micro-waveguide is investigated under small signal approximation (1-12 mW pump). The quadratic relationship between the fundamental and the second harmonic powers is well established. The SHG conversion efficiency of the micro-waveguide is measured to be 335%/W at low pump powers. Considering the fiber coupling loss, the on-chip normalized conversion efficiency is 164%/(W·cm2). Compared with the theoretical prediction of 555%/(W·cm2), the obtained SHG normalized conversion efficiency still has a large room for improvement. As the pump power continues to increase, the quadratic relationship between them gradually degrades to linear and gradually converges to saturation. When the pump power reaches 1 W (the actual on-chip pump power is 750 mW), the second harmonic (SH) power reaches 429 mW, with an absolute on-chip conversion efficiency of 57.2%. In addition, the fiber coupling loss is only 1.2 dB/facet. The overall absolute conversion efficiency of the device is close to 30% at 1 W pump light input and remains stable over one hour. The device can maintain stable frequency conversion under watt-scale power, which shows the great potential of MgO∶PPLNOI micro-waveguide for realistic applications. Our PPLNOI waveguide also has excellent performance in the SFG process. Under 5-mW signal light, the conversion efficiency saturates when the input pumping exceeds 220 mW, and the absolute conversion efficiency is up to 139% in our experiment. This corresponds to the up-conversion of about 70% of the signal photons. The PPLNOI micro-waveguide has the advantages of low insertion loss, high scalability, and high performance. Its efficient frequency conversion provides a new choice for infrared light detection.ConclusionsWe demonstrate the fabrication process of PPLNOI micro-waveguides by UV lithography and dry etching on a 3-μm thick LNOI platform. Results show that the micro-waveguide exhibits an SHG conversion efficiency of 335%/W at low powers and an absolute conversion efficiency of 57% under 1 W pump power. When the pump power reaches 300 mW, the absolute SFG conversion efficiency of the signal light reaches 139%, achieving efficient frequency up-conversion. Our micro-waveguide is well compatible with optical fiber, featuring low insertion loss and better overall performance. It not only balances the normalized efficiency, coupling efficiency, and device length but also achieves highly efficient absolute frequency conversion at high power input, which makes LNOI micro-waveguides highly attractive for practical applications and advancing other areas of nonlinear optics.

ObjectiveLithium niobate on insulator (LNOI) has emerged as a promising integrated photonic platform for on-chip optical interconnection and optical communications, which is due to its outstanding characteristics, such as excellent electro-optic properties and strong optical nonlinearity. Diverse important active photonic circuit components have been proposed, including electro-optic modulators and wavelength converters. In particular, the electro-optic bandwidth of the LNOI modulator has reached up to 100 GHz and beyond, thus improving the data capacity of optical links significantly. However, with the continuous data capacity growth, the modulation rate of a single modulator will be challenging to meet the application demands. Therefore, developing a series of advanced optical multiplexers is necessary to further improve the data capacity. Recently, some advanced optical (de)multiplexing technologies have been intensively studied and reported in the LNOI platform, such as wavelength division multiplexing, polarization division multiplexing, and mode division multiplexing. Multidimensional hybrid multiplexing technologies are more important for further improving the data capacity of optical links. Among them, the dual-polarization mode (de)multiplexer (MMUX) has become a promising device as it can achieve multichannel multiplexing by only employing a single-wavelength laser, which thus lessens the cost and power consumption of optical links. However, challenges remain in realizing dual-polarization MMUX in the LNOI platform compared with the silicon-on-insulator (SOI) platform. Specifically, mode hybridization will occur in special width waveguides due to the vertical asymmetry and material anisotropy of the LNOI platform, which will introduce a lot of mode crosstalk in the bus waveguide. Therefore, we propose and demonstrate a dual-polarization MMUX with six data channels in the LNOI platform, with a subwavelength-grating taper adopted to engineer the dispersion of different modes to suppress the mode hybridization.MethodsWe employ the finite element analysis method and 3D finite-difference time-domain (3D-FDTD) method. First, we calculate the effective refractive indices of different modes in the straight waveguide as a function of the width of the waveguide (Fig. 2). The results show that the mode hybridization occurs at some specific waveguide widths when the light propagates along with the Y direction, which will introduce inter-mode crosstalk when the waveguide width changes gradually. Then, we adopt the SWG taper waveguide to suppress the mode hybridization. To design the SWG taper waveguide, we input a 1550 nm light with TM0 and TE0 mode to the left of the taper waveguide, and simulate the insertion loss and crosstalk of TM0 and TE0 mode channel as a function of the length of the SWG taper and ordinary taper waveguides respectively by the 3D-FDTD method (Fig. 5). Meanwhile, we select the 3D-FDTD simulation method to optimize the width of different taper waveguides and the coupling length of different mode coupling regions (Fig. 7).Results and DiscussionsAs proof of the concept, we fabricate a pair of dual-polarization MMUX and employ 12 TE-polarization grating couplers to interface the waveguides to optical fibers (Fig. 8). Then, an amplified spontaneous emission (ASE) and optical spectrum analyzer (OSA) are utilized to characterize the static performance of the fabricated device. The measured transmission spectra of different optical links are normalized by the PSRs with the same parameters, which are fabricated close to the device. The insertion losses of TE0, TM0, TE1, TM1, TE2, and TM2 mode channels are below 1.7 dB, 1.4 dB, 1.7 dB, 2.8 dB, 2.5 dB, and 3.1 dB respectively, while the crosstalk of TE0, TM0, TE1, TM1, TE2, and TM2 mode channels are below -10.5 dB, -17.3 dB, -10.9 dB, -11.6 dB, -10.1 dB, and -12.0 dB respectively, within the wavelength range of 1525-1565 nm (Fig. 9). Finally, the dynamic data transmission experiment with a total capacity of 1.52 Tbit/s net data rate has also been conducted (Fig. 10). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental demonstration of dual-polarization MMUX with six mode channels in the LNOI platform. The proposed device has a huge potential in applications of high-speed and large-capacity optical interconnection. Thus, it has the potential to be followed by many researchers and will be applied to a large number of relevant investigations.ConclusionsIn summary, we propose, design, and demonstrate a dual-polarization MMUX with six mode channels based on the LNOI hybrid platform. The SWG taper waveguide is adopted to suppress the mode hybridization along the Y direction of the LNOI platform. The measured insertion loss and crosstalk of the fabricated device are lower than 3.1 dB and -10.1 dB respectively, within the wavelength range of 1525-1565 nm. Additionally, a high-speed data transmission experiment with a net data rate of 1.52 Tbit/s is demonstrated. Meanwhile, the fabricated device can be combined well with wavelength division multiplexing technology to realize a huge data transmission capacity. The results show that the fabricated dual-polarization MMUX has sound static and high-speed data transmission performance, which can be expected to be employed as the key to future high-speed and large-capacity optical interconnection.

SignificanceWith the exponential growth in data transmission, optical interconnection technology has replaced traditional electrical interconnection technology and become the mainstream for low-loss and high-speed transmission over medium and long distances. By utilizing photons for data transfer, optical interconnections offer significant advantages such as large bandwidth and low latency, which are crucial in meeting the demands of modern communication systems. The photodetector, which converts optical signals into electrical signals, is the core component of optical interconnection systems. Rapid advancements in telecommunications and data processing necessitate photodetectors with exceptional speed and efficiency. Among photodetectors, waveguide-coupled designs have garnered significant attention due to their compact size, high bandwidth, and easy integration with other optoelectronic devices. These attributes are critical for the development of integrated photonic circuits, which are essential for applications in data centers, telecommunications, and emerging fields such as quantum computing. Traditional high-performance InGaAs photodetectors have long been the standard in near-infrared communications. Meanwhile, Ge/Si photodetectors are rapidly advancing due to silicon photonics, which enables large-scale, low-cost production compatible with existing semiconductor manufacturing processes. The need for higher data rates and lower power consumption drives the transition from electrical to optical interconnections in communication networks. Photodetectors are crucial in this transition because they directly impact the overall performance of optical communication systems. The integration of photodetectors with waveguides not only enhances the bandwidth but also allows for the development of more compact and efficient photonic devices. This integration is essential for the continued advancement of optical interconnection technologies, expected to play a dominant role in future communication infrastructures.ProgressWe first introduce the mainstream choices for high-speed photodetectors, primarily including InGaAs photodetectors and Ge/Si photodetectors. Then we discuss the typical structures and research advancements of these two major types of photodetectors. The preferred structure for InGaAs photodetectors is the uni-traveling-carrier (UTC) structure, addressing the slow hole transport issue in III-V materials compared to the PIN structure. For example, the research group led by Seeds A J at University College London reported a high-speed evanescently coupled photodetector with a 3 dB bandwidth of 110 GHz. Li et al. from the University of Virginia reported a high-speed waveguide-coupled photodetector with a bandwidth exceeding 105 GHz, fabricated using MOCVD on an InP substrate (Fig. 1). Additionally, heterogeneous integrations of III-V photodetectors on silicon, primarily through direct epitaxy and wafer bonding, have received widespread attention. Sun et al. fabricated an improved single-carrier (MUTC) III-V photodetector on a Si substrate, achieving a responsivity of 0.78 A/W and a 3 dB bandwidth of 28 GHz under a reverse bias voltage of 3 V (Fig. 2). For silicon-based group IV photodetectors, they mainly include all-silicon photodetectors and germanium-silicon photodetectors. Researchers have achieved all-silicon photodetectors by introducing new absorption mechanisms or device structures. Intel reported a waveguide-coupled all-Si photodetector with a 3 dB bandwidth of 15 GHz (Fig. 3), achieving a responsivity of 1.6 A/W at a reverse bias voltage of 5.93 V with an active region length of 300 μm. Germanium, similar to silicon, is highly compatible with Si CMOS processes. With advancements in silicon photonics technology, waveguide-coupled Ge/Si photodetectors have become the most widely researched Si-based group IV photodetectors due to their excellent high-speed performance and mature process flow. Lischke S et al. proposed a lateral Ge/Si photodetector with a 3 dB bandwidth up to 265 GHz by reducing the width of the fin-shaped Ge absorption region (Fig. 6), marking the highest bandwidth achieved for Ge/Si photodetectors to date. The width of the fin-shaped Ge absorption region is only 100 nm, effectively reducing carrier transit time and enhancing the high-speed performance of the Ge photodetector.Conclusions and ProspectsPhotodetectors, as the core components of optical receivers, have gradually matured over the years. Our study introduces the current development of two types of waveguide-coupled photodetectors, including III-V and IV group photodetectors, each with its advantages and characteristics. Benefiting from III-V materials’ superior light absorption and high electron mobility, InP-based InGaAs photodetectors can achieve ultra-high-speed light detection based on the UTC structure, becoming the most mature photodetectors. On the other hand, IV group photodetectors, primarily Ge/Si photodetectors, are compatible with Si CMOS processes and possess inherent advantages in integration. With advanced processing technologies on silicon photonics platforms, higher processing accuracy and integration can be achieved. These features enable the fabrication of finer device structures and make ultra-high-speed Ge/Si photodetectors comparable to InP-based high-speed photodetectors. The future development of high-speed photodetectors still faces several challenges. Although Ge/Si and InGaAs photodetectors with a 3 dB bandwidth exceeding 200 GHz have been reported, their responsivity is not satisfactory. Balancing bandwidth improvement while maintaining good responsivity is an important research topic that may require the introduction of process-compatible new materials (high mobility and high absorption coefficient) or novel high-speed device structures. Furthermore, as devices’ bandwidth increases, the application scenarios of detectors in microwave photonics links will gradually expand. Unlike the low optical power input and high sensitivity detection in optical communications, this scenario requires high saturation power due to high-power input based on large bandwidth. However, large-bandwidth devices typically employ small-sized structures, making it challenging to produce photodetectors that are both high-speed and high-power-saturation. Therefore, further innovation in carrier extraction and heat dissipation of the devices is necessary.

SignificanceWith the rapid advancement of the Internet of Things, Industry 4.0, and artificial intelligence, the global demand for communication capacity has grown exponentially. Looking toward the future, the industry is focused on researching and exploring the next-generation mobile communication technology (6G). 6G aims to leverage low, medium, and high-frequency spectrum resources for seamless global coverage, achieving peak data rates of Tbit/s. Photonic terahertz communication, offering advantages such as large bandwidth, low loss, and seamless integration with fiber optic networks, stands as a pivotal technology for future terahertz communications. Terahertz photodetectors play a critical role in these systems and have attracted considerable attention. In this paper, we summarize recent advancements in III-V terahertz photodetectors, germanium-silicon terahertz photodetectors, and heterogeneous integrated terahertz photodetectors within the communication band. This paper provides detailed insights into structural optimizations, advancements in fabrication technologies, and breakthroughs in achieving high bandwidth and power output for these photodetectors. By reviewing these developments, we aim to provide valuable guidance for the future development of high-speed, high-power photodetectors.ProgressPhotodetectors can be divided into two types based on the input light mode surface-incident and waveguide-incident photodetectors. From a bandwidth perspective, traditional surface-incident PIN photodetectors face a trade-off between bandwidth and responsivity. Increasing the thickness of the intrinsic absorption layer improves responsivity but also increases the transit time of photogenerated carriers, resulting in reduced bandwidth. Thus, bandwidth and responsivity are mutually limiting and difficult to balance. To achieve terahertz bandwidth, the thickness of the absorption layer is typically reduced, which decreases the transit time and reduces the device geometry to create terahertz photodetectors. However, the inherent bandwidth-responsivity trade-off limits further improvement in the device’s bandwidth-efficiency product. In contrast, waveguide-incident photodetectors overcome this inherent trade-off by decoupling the optical absorption process from the carrier transport process. The surface-incident III-V PIN photodetector achieves a bandwidth of 110 GHz and a bandwidth-efficiency product of 35 GHz. The latest waveguide germanium-silicon PIN photodetector achieves a bandwidth of 240 GHz and a bandwidth-efficiency product of 86.5 GHz, with a maximum bandwidth of 265 GHz (Fig. 15). From a power perspective, under high optical power conditions, photogenerated electron-hole pairs accumulate in the depletion region or at the heterogeneous interface, forming space charges. This reduces the electric field strength in the depletion region, causing the electric field to collapse, reducing the carrier drift velocity, and ultimately leading to a significant reduction in device bandwidth, responsivity, and output power. Compared to surface-incident photodetectors, waveguide-incident photodetectors experience severe local space charge effects that significantly limit their saturated output power. Traditional PIN photodetectors are limited by the slow drift velocity of the holes and strong space charge effects, which limit the output power of the device. To mitigate the space charge effect, a uni-traveling-carrier photodetector has been proposed. In this structure, the optical absorption process is decoupled from the carrier drift process by P-type doping of the absorption layer. Photogenerated holes in the P-type doped absorption layer are collected by the P-electrode through relaxation oscillation, while photogenerated electrons move to the collection layer by diffusion and are then collected by the N-electrode. In this process, only photogenerated electrons drift as effective carriers. This structure decouples the optical absorption process from the photogenerated electron transport process. Since the electron drift speed is much higher than that of holes, this structure effectively reduces the device transit time. At the same time, space charges in the depletion region can be quickly transported to the electrodes, effectively suppressing the space charge effect. On this basis, III-V uni-traveling-carrier photodetectors have achieved excellent performance by optimizing the epitaxial layer structure. The surface-incident uni-traveling-carrier photodetector achieves a bandwidth of 330 GHz, and provides an output power of -3.2 dBm@320 GHz (Fig. 12). The waveguide uni-traveling-carrier photodetector achieves a bandwidth of 220 GHz, with an output power of -1.69 dBm@215 GHz (Fig. 10). As system functions become richer and performance indicators improve, the demand for device integration increases. Therefore, integrated terahertz photodetectors and multifunctional integrated chips based on terahertz photodetectors are important research directions in photonic terahertz communication. By integrating high-performance photodetection, photonic terahertz signal processing, and high-performance terahertz signal generation functions into a single chip, system cost and power consumption would be greatly reduced, and system performance is improved. Integrated photodetectors with bandwidths of 70, 155, and 110 GHz have been implemented on SOI, silicon nitride, and thin-film lithium niobate platforms, respectively (Table 1).Conclusions and ProspectsThe terahertz photodetector is a core device in terahertz optical communication systems. We summarize the recent progress in III-V terahertz photodetectors, germanium-silicon terahertz photodetectors, and heterogeneous integrated terahertz photodetectors. III-V materials with high electron mobility are widely used in the fabrication of terahertz photodetectors. At present, terahertz photodetector devices are relatively small in size and are usually fabricated by electron beam lithography. This method is highly precise and capable of producing ultra-small devices, but it is difficult to scale up for mass production. Therefore, it is necessary to develop stepper exposure methods based on ultraviolet/deep ultraviolet lithography to fabricate large-scale, high-yield terahertz photodetector chips. For germanium-silicon photodetectors, a terahertz bandwidth germanium-silicon photodetector has been realized using custom technology. The bandwidth of germanium-silicon photodetectors based on general processes has reached 103 GHz (Table 1). The device bandwidth is expected to be further improved by optimizing the device structure and electrode configuration. Heterogeneous integrated photodetectors based on wafer bonding or epitaxial growth have demonstrated 100 GHz bandwidth. The next step is to achieve ultra-large bandwidth and multi-function integration of heterogeneous integrated chips. This will meet the bandwidth, output power, responsivity, and integration requirements of photonic terahertz communication systems.

SignificanceSilicon is an indirect bandgap semiconductor that cannot emit light efficiently. In contrast, Ⅲ-V compound semiconductors such as AlGaAs/GaAs and InGaAsP/InGaAlAs/InP are direct bandgap semiconductors widely used for fabricating efficient electrically driven laser devices. As silicon-based photonic integrated circuits enter commercial application, integrating Ⅲ-V compound semiconductor lasers on silicon has become a key bottleneck for its future development.ProgressThree main kinds of approaches have been developed aimed at integrating Ⅲ-V semiconductor laser sources on silicon photonic chips. The hybrid integration approach mounts prefabricated semiconductor laser chipsets on silicon photonics substrates by means of precision flip-chip bonding between gold pads. To achieve high optical coupling efficiency between the laser chipset and the silicon waveguide, the main technical challenges include repeatable sub-micron three-dimensional alignment and optical mode matching. Precision alignment mainly relies on high-precision equipment in the horizontal direction and carefully designed mechanical structures in the vertical direction, while optical mode matching relies on predesigned mode converters. This technology has been put into small-volume production but faces challenges in terms of productivity, yield, and cost. The heterogeneous integration approach is based on transferring Ⅲ-V active devices or films onto silicon by means of transfer printing or die-to-wafer bonding. In transfer printing, prepared Ⅲ-V lasers are picked up by an elastomer stamp and attached to a silicon substrate by van der Waals force or by an adhesion agent. Compared with flip-chip bonding, transfer printing is a flexible process that can integrate multiple devices of different kinds in one step. Optical coupling with the underlying silicon waveguide is usually achieved via evanescent coupling. In die-to-wafer bonding, Ⅲ-V epitaxial wafers are diced into desired sizes and placed with their active side up on a carrier plate by temporary bonding. The carrier plate with the dies is then activated in plasma and flipped over to bond the dies to the silicon photonics wafer. The carrier plate is then removed, and the Ⅲ-V dies are thinned to remove their original Ⅲ-V substrate, leaving only the active epi-layer attached to the silicon wafer. Semiconductor lasers are then fabricated in the active epi-layer, precisely aligned to the underlining silicon waveguide by means of photolithography alignment markers to ensure high-efficiency evanescent coupling. This technology has successfully realized wafer-scale production. While promoting productivity, the yield of both transfer printing and die-to-wafer bonding approaches is still being improved. The direct epitaxy of Ⅲ-V semiconductors on silicon is attractive as a truly wafer-scale production approach but faces significant challenges in terms of crystal lattice mismatch, thermal mismatch, and anti-phase domains at the epi-interface which leads to high stress and high defect densities in the Ⅲ-V epi-layer. Various schemes have been developed, including blanket growth and selective area growth. In blanket growth, thick buffer layers are needed to reduce the defect density in the Ⅲ-V active layer, which can prevent optical coupling between the Ⅲ-V active layer and the underlying silicon waveguide. Growth in etched pits can align the active layer with the silicon waveguide but faces problems in laser facet quality. Using quantum dots instead of bulk or quantum well active layers significantly mitigates adverse effects of defects on laser efficiency and lifetime. Vertical selective area growth can produce high-quality Ⅲ-V crystals by means of defect-trapping, but micro-sized material cannot support electrodes for current injection. Horizontal selective area growth enables epi-growth of Ⅲ-V materials and quantum-well active structures in the lateral direction, forming larger-sized Ⅲ-V films co-planar with the silicon waveguide layer, therefore demonstrating promising potentials for electrically pumped semiconductor lasers efficiently butt-coupled with the silicon passive waveguide.ConclusionsⅢ-V lasers on silicon photonics chips have been realized through hybrid integration, heterogeneous integration (including transfer printing and die-to-wafer bonding), and direct epitaxy. While hybrid and die-to-wafer bonding approaches have been commercialized in small to medium-volume production, further improvement in terms of their productivity and yield is needed. The direct epitaxy approach as a true wafer-scale remains an attractive long-term solution requiring substantial research and development.

SignificanceSilicon photonics combines the high speed and broad bandwidth of optical signals with high-density and low-cost fabrication of the complementary metal oxide semiconductor (CMOS) technology, and it has been an attractive technology for various applications ranging from data centers to biosensing. However, silicon is not capable of building several active optoelectronic devices for fully integrated photonic circuits. For example, the indirect bandgap of silicon makes it challenging to achieve efficient light sources, the absence of the Pockels effect prevents silicon from building high-speed linear electro-optic modulators, and the absorption cutoff wavelength of 1100 nm makes silicon incompatible with telecom-band photodetection. A common strategy to overcome such limitations is the heterogenous/hybrid integration of material technology suitable for active optoelectronic devices, such as the epitaxy growth of germanium for telecom-band photodetectors and wafer-bonding of III-V semiconductors for on-chip lasers and modulators. However, such integration has problems including the lattice mismatch during epitaxy, high cost, low yield of bonding, and optical mode mismatch between different materials. Therefore, it is necessary to develop novel material platforms that can provide high-performance active devices with CMOS-compatible fabrication. In this regard, colloidal quantum dot (CQD) semiconductors featuring excellent optoelectronic properties, low-cost chemical synthesis, and CMOS-compatible solution-based fabrication emerge as a competitive material platform for active devices integrated into silicon photonic chips. Due to their continuously tunable bandgap from UV to THz enabled by the quantum confinement effect, near-unity photoluminescence quantum yield, narrow emission linewidth, and highly tunable carrier transport, the potential applications of the CQD have been demonstrated by the commercialization of CQD-enhanced liquid crystal display by Samsung company and the short-wave infrared camera of SWIR Vision Systems company. Meanwhile, their applications in light-emitting diode display, solar cells, and quantum emitters are extensively researched. In this respect, the 2023 Noble Prize in Chemistry was awarded to Alexei Ekimov, Louis Brus, and Moungi Bawendi for the discovery and development of CQDs. Over the last decade, there have been several studies on CQD active devices integrated into silicon photonic chips, including waveguide-integrated photodetectors, light-emitting diodes, and optically pumped lasers. Thus, it is necessary to provide readers of different academic backgrounds with a full picture of CQD materials, including their synthesis route, thin film fabrication, and optoelectronic properties related to the chip-integrated active devices. Additionally, it is high time to update the latest progress in chip-integrated CQD active devices and discuss the possible route for their future development.ProgressFirst, the colloidal synthesis of CQDs and their solution-based thin film deposition are introduced, with an emphasis on the role of surface organic ligands in governing the solution stability and controlling the optoelectronic properties of CQDs. The optical properties of CQDs related to their integration on silicon photonic chips are then summarized. Specifically, their spectral coverage from UV to THz range is achieved by quantum confinement effect and heterostructure band alignment, and their complex refractive index can be tuned from 1.7 to 2.7 by the CQDs material composition, surface ligand and film deposition strategy (Table 1). Meanwhile, the optical gain characteristics (gain magnitude, gain threshold, and gain lifetime) and their measurement methods (transient absorption and variable stripe length methods) are presented, with the optical gain properties of the most employed CQDs summarized in Table 2. Regarding the electrical properties of CQDs, we introduce ligand exchange processes that provide conductive CQD thin films with by-design doping types and magnitude, which is the core of fabricating high-performance active optoelectronic devices. After introducing the fundamental optoelectrical properties of CQDs, we present the fabrication level and summarize the patterning strategies of CQD thin films including lithography, ink-jet printing, 3D printing writing, and transfer printing, thus demonstrating the feasibility of CQD-based active device integration with silicon. In the next section, we summarize the latest progress in chip-integrated CQD-based photodetectors and light sources. In terms of CQD-based photodetectors, plasmonic-Si hybrid waveguide integrated HgTe CQD-based photoconductor and SiN waveguide integrated PbS CQD-based photodiodes are presented. Additionally, we show their performance including the responsivity, 3 dB bandwidth, and external quantum efficiency in Table 3. Their current limited photodetection performance is attributed to factors such as high dark current from a photoconductive configuration, low carrier mobility from solid-state ligand exchange, and photocurrent saturation due to the evanescent coupling between the photodetector and the waveguide. Regarding the chip-integrated CQD-based light sources, the electrically pumped light-emitting diode has poor outcoupling efficiency of below 1% due to a lack of emission directionality. On the other hand, waveguide-coupled CQD-based lasers have attracted more research interest. We summarize the structure and performance of these lasers in Table 4 and present their developments in detail by dividing them into additive and substrative manufacturing categories. For additive manufacturing, the self-assembled supraparticle and microring resonator lasers made of CQDs are demonstrated and outcoupled by waveguides. We also present template-assisted CQD microring lasers with predefined patterns, with higher flexibility and controllability shown. Plasmonic waveguide integrated CQD lasers are also developed to demonstrate coherent output sources at sub-diffractive scale. Meanwhile, with a fully CMOS compatible fabrication process, subtractive manufacturing of a sandwich-structured SiN/CQD/SiN thin film has been developed by the van Thourhout group from Gent University, with successful demonstrations of low-threshold picosecond laser pumped micro-disk lasers and quasi-continuous-wave pumped diffracted feedback lasers.Conclusions and ProspectsWith the advances in synthesis, device physics, and CMOS compatible thin film fabrication of CQDs, their integration with silicon photonic chips is drawing increasing attention. We expect that the advantages of CQDs can be better leveraged in the direction of long-wavelength infrared photodetectors, and more interestingly, the electrically pumped on-chip lasers that are in high demand in current silicon-based optoelectronic technology. The development of electrically pumped on-chip CQD lasers will rely on the invention of novel CQD materials with better optical gain properties, the rational design of electrical and optical structures, and their extension to infrared wavelength.

ObjectiveA tunable laser is one of the crucial technologies in optical networks due to its advantage of flexibly switching output wavelengths. After years of research, tunable semiconductor lasers have developed various solutions. Super-structure grating distributed Bragg reflector (SSGDBR) tunable lasers, modulated grating Y-branch distributed Bragg reflector (MGY-DBR) lasers, and chirped sample grating distributed reflector (CSGDR) tunable lasers can achieve wide-range tuning. External cavity lasers (ECL), distributed feedback (DFB) lasers, and vertical cavity surface emitting lasers (VCSELs) are typical structures used for tunable lasers. The cavity length of ECL can be very long, resulting in a very narrow linewidth. However, its large volume makes it difficult to integrate with other devices on a single chip. The tuning range of a single DFB laser is only 3-5 nm, which cannot meet the requirements for wide-range tuning. To achieve wide-range tuning, multiple DFB lasers with different center wavelengths can be integrated into a DFB array. Although the manufacturing process of DFB lasers is mature, ensuring the integration of multiple lasers on the same chip remains challenging. VCSELs have a short cavity length and high reflectivity, resulting in a large longitudinal mode spacing and good single longitudinal mode performance. However, they exhibit multiple transverse modes and a larger linewidth, which makes integration with other devices challenging. To address the limitations of the aforementioned lasers, we design and propose a monolithic integrated tunable laser-multi-channel interference (MCI) laser. This laser achieves wavelength tuning based on the thermal optical effect by selecting modes through arm interference of different lengths. Unlike the lasers mentioned earlier, the MCI laser does not require a grating for mode selection. Additionally, each arm can independently change the phase and control the laser wavelength, significantly simplifying the laser production process and increasing production tolerance. Through multiple rounds of design and iteration, our study has successfully verified the feasibility of the scheme and achieved transmitter optical subassembly (TOSA) packaging and miniaturized integrated components for this laser.MethodsMCI laser includes an active section for optical gain, a semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA) section for amplifying output optical power, and a multi-channel interference region for mode selection. The multi-channel interference section is composed of a common phase section for tuning longitudinal modes and a 1×8 multi-mode interferometer (MMI) for beam splitting, with 8 arms of different lengths. Each arm end is equipped with a multimode interference reflector (MIR) that reflects the total light to the active section, and a metal thermal electrode is positioned above each arm. The 8 arms independently adjust the phase of the light field based on the thermal optical effect, enabling interference to obtain a reflection spectrum dominated by a single reflection peak. Adjusting the phase interference of the 8 arms enhances coarse wavelength adjustment while adjusting the longitudinal mode of the common phase zone facilitates fine wavelength adjustment. The shape of the entire reflection spectrum can be optimized by adjusting the differences in arm lengths. Optimizing these differences is crucial for achieving better single-mode performance of MCI lasers. During the optimization of arm length differences, it is essential to consider suppressing adjacent longitudinal modes and other modes far from the main reflection peak simultaneously. We propose a method using particle swarm optimization (PSO). The PSO algorithm is combined with the multi-mode rate equation to optimize the laser arm lengths and obtain the optimal arm length design method, thereby achieving a better reflection spectrum across the entire wavelength band. The signal-to-mode suppression ratio (SMSR) of the wavelength at 1515 nm, at the edge of the gain spectrum, serves as the optimization index for the PSO algorithm, ensuring it exceeds 45 dB across the entire band and controls the half-width of the main peak to suppress adjacent longitudinal modes. After iterative analysis, a set of eight arm lengths is determined: 140.00, 268.28, 384.64, 521.80, 526.80, 674.00, 681.25, and 750.41 μm.Results and DiscussionsThe MCI laser achieves a tuning range of 48 nm covering the C++ band (1524-1572 nm). It boasts an SMSR exceeding 46 dB and a fiber-coupled output power exceeding 16.5 dBm. Both SMSR and output power depend on the gain of the active region. The peak of the gain spectrum maximizes gain, minimizes threshold current, maximizes SMSR, and optimizes output power. Moving away from this peak increases threshold current, reducing SMSR and output power accordingly. The gain spectrum steepens towards shorter wavelengths, accelerating reductions in SMSR and output power in that direction. Frequency deviation from the international telecommunication union (ITU) standard remains within ±0.5 GHz across all channels and is wavelength-independent. Further optimization can be achieved by adjusting the TEC1 operating temperature. Wavelength drift is less than ±1 pm, demonstrating excellent temperature control and wavelength locking performance. Output optical power for 120 wavelengths remains fixed within different values (12-16 dBm), and the power deviation is maintained within ±0.1 dB. The reverse bias extinction ratio (ER) in the SOA region exceeds 40 dB, and all wavelength channels achieve a narrow linewidth of less than 150 kHz. The ITLA’s total power consumption is less than 3 W under 75 ℃ environment.ConclusionsA new type of monolithic wide-range tunable semiconductor laser—MCI laser, is proposed. This device utilizes thermal-optical effects and 8-arm interference enhancement to adjust reflection peaks and longitudinal modes, achieving wavelength tuning akin to a distributed Bragg reflector (DBR). With the absence of grating structures, it offers advantages in fabrication simplicity and tolerance. The integration of offset quantum wells technology for active and passive components reduces regrowth complexity. The MCI laser features a wavelength tuning range exceeding 48 nm, SMSRs greater than 46 dB, Lorentzian linewidths less than 150 kHz, and consumes less than 50 mW for total thermal tuning power. The MCI laser chip, thermoelectric cooler (TEC), and wavelength locking device are packaged into a TOSA box, achieving an integrated tunable laser assembly (Nano-ITLA) measuring only 25.0 mm×15.6 mm×6.5 mm. Fiber-coupled output powers exceed 16.5 dBm, covering 120 ITU channels with frequency deviations less than ±0.5 GHz in the C++ band. Under wavelength locking and power balancing control, wavelength drifts are less than ±1 pm, power jitters are less than ±0.1 dB, and the reverse-biased SOA section exhibits extinction ratios greater than 40 dB. The MCI wide-range tunable laser demonstrates excellent potential for applications in coherent optical communication.

ObjectiveNarrow linewidth semiconductor lasers are crucial in coherent optical communications due to their low phase noise. The rapid growth in network capacity demands advanced modulation formats with stringent phase stability requirements, necessitating lasers with linewidths of 100 kHz or lower. The square Fabry-Perot (FP) coupled cavity consists of a square microcavity and an FP cavity directly connected. The FP cavity acts as the main gain component, while the square microcavity serves as the selective reflective end facet. The strong coupling between the whispering gallery mode and the FP mode achieves a high side-mode rejection ratio and efficient coupling output, though the laser linewidth is typically in the MHz range. We aim to drastically narrow the linewidth of the square FP coupled-cavity laser for coherent optical communications.MethodsUsing the finite element method, we simulate the reflectance of an 18 μm side-length square microcavity, identifying seven transverse modes with reflectance greater than 0.7 within twice the longitudinal mode spacing. We also simulate the mode characteristics of a coupled cavity with an FP cavity length of 550 μm and a width of 2 μm. Analyzing the square cavity reflectance, coupled-mode Q-factor, and the fundamental transverse mode proportion in the FP cavity, we determine that the coupled mode corresponding to the sixth-order whispering gallery mode is preferentially excited in the actual device. Subsequently, we fabricate square FP coupled-cavity lasers using a 3 quantum-well AlGaInAs/InP epitaxial wafer with dimensions of side length a=18 μm, FP cavity width w=2 μm, and length L=550 μm. The deeply etched laser waveguide’s optical confinement factor is approximately 0.34%, effectively reducing the Lorentzian linewidths.Results and DiscussionsWe measure the single-mode fiber-coupled output power and voltage characteristics of the square FP coupled-cavity laser, finding a resistance of about 7 Ω and a single-mode fiber-coupled output power of 13 mW. The main mode is at 1550.5 nm with a side-mode suppression ratio of 47 dB for injection currents ISQ=35 mA and IFP=165 mA. The spectrum’s envelope aligns with the square microcavity’s reflectance spectrum. With a fixed square microcavity injection current ISQ=18 mA, we observe the lasing spectrum variation with the FP cavity injection current IFP. Below the threshold current, the fundamental mode of the square microcavity at 1519.2 nm is visible. As IFPincreases, the coupled mode lases at about 1521 nm, separated from the fundamental whispering gallery mode by 1.6 nm. The anti-symmetric fundamental mode in the square microcavity, having the highest Q-factor, is preferentially excited. The lasing mode forms by coupling the sixth-order whispering gallery mode with the FP mode. Near IFP=70 mA, the lasing mode hops from 1521 nm to 1548 nm, corresponding to twice the longitudinal mode spacing of the square microcavity. We measure the frequency noise power spectral density of this laser using the self-homodyne optical coherent receiver method and obtain a Lorentzian linewidth as low as 233 kHz, maintaining around 300 kHz with stable single mode lasing.ConclusionsWe design a narrow linewidth square FP coupled-cavity laser with a 3 quantum-well AlGaInAs/InP epitaxial wafer and a low transverse optical confinement factor. The square microcavity has a side length of 18 μm, and the FP cavity measures 2 μm in width and 550 μm in length. Simulations and experiments indicate that the coupling mode corresponding to the higher-order whispering gallery mode of the square microcavity is excited. The laser’s maximum single-mode fiber-coupled output power is 13 mW, with a maximum side-mode suppression ratio of 47 dB, and a Lorentzian linewidth of 233 kHz.