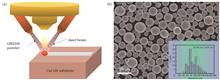

ObjectiveAdditive manufacturing of Cu/Ni dissimilar metals, integrating high-thermal conductivity, high strength, high reliability, and low cost, is one of the best choices for the generation of liquid rocket engines, capable of achieving material-structure–function engine integration. Currently, the main challenges faced in the preparation of GH4169 using laser-directed energy deposition (LDED) technology on CuCrZr substrates are the high-laser reflectivity and thermal conductivity of copper alloys, as well as the considerable differences in the physical properties of the two alloys, making it difficult to achieve defect-free metallurgical bonding. Stable process manufacturing and control of microstructural properties are also challenges. Herein, we use surface pretreatment processes followed by additive manufacturing to solve the problems of high reflectivity of Cu alloys and interface metallurgical defects and prepare CuCrZr/GH4169 dissimilar metals.MethodsThis study utilizes five processes, namely thermal spraying, cold spraying, electroplating, physical vapor deposition (PVD), and powder spreading, for surface pretreatment of the CuCrZr alloy. On the pretreated surfaces of the CuCrZr substrates, three processes are employed for single-track cladding experiments; Process 1: laser power set at 4.5 kW, and scanning speed set to 1000 mm/min, without powder feeding; Process 2: laser power set at 4.0 kW, scanning speed set at 1000 mm/min, and a powder feeding rate of 35 g/min, and Process 3: laser power set at 4.5 kW, scanning speed set at 1000 mm/min, and powder feeding rate of 40 g/min. The optimal process is selected for overall additive manufacturing of CuCrZr/GH4169 alloy. Microstructural observations are conducted on the interface of single-track cladding specimens (perpendicular to the laser scanning direction) and the interface of overall dissimilar metals specimens. Ultrasonic nondestructive testing and tensile performance testing are performed on the dissimilar metals specimens.Results and Discussions1) Single-track cladding deposition GH4169 experiments are conducted on CuCrZr substrates using different surface pretreatments. The results for thermal spraying (Fig. 6) and cold spraying (Fig. 7) samples are excellent . The thermal spraying samples formed a stable melt pool without microcracks, pores, or local unmelted areas at the interface. In the cold spraying samples, local unmelted areas appeared at the edges of the melt pool when the coating thickness increased to 150 μm. However, the electroplating (Fig. 8) and PVD (Fig. 8) samples did not produce stable melt pools, and there were obvious microcracks and local unmelted areas between the coating and the weld track. The coating prepared by powder spreading process (Fig. 8) showed many unmelted adhesive powders around the weld track, poor continuity of the weld track, unstable melt pool fusion line, and small penetration depth. The thermal spraying experiment yielded the best results. By comparing the main parameters of single-track cladding, the optimal process was selected: thermal spraying was used to deposite the GH4169 alloy coating with 100 μm thickness on CuCrZr substrate, Process 1 was used to remelt the first layer, followed by Process 2 for deposition.2) The prepared samples exhibited good bonding characteristics between the two materials. Nondestructive testing results did not reveal major defects (Fig. 10). The interface area of the samples along the deposition direction from the bottom to the top parts can be divided into five regions: CuCrZr substrate, columnar crystal, diffusion, Cu element diffusion, and GH4169 regions (Fig. 11). The tensile strength of the laser-directed deposited CuCrZr/GH4169 dissimilar metals along the deposition direction was 280 MPa±4.24 MPa, with the fracture occurring at the interface, slightly toward the copper alloy side, indicating a ductile fracture.ConclusionsThis study primarily investigates the impact of surface modification on the laser reflectivity of copper alloys. Various surface modification processes, including thermal spraying, cold spraying, electroplating, PVD, and powder spreading, were used to prepare nickel-based alloy coatings with different compositions and thicknesses on copper alloy surfaces. After determining the optimal preparation process, coating composition, and thickness, the overall material deposition process was explored. The main conclusions are as follows:1) The results of the single-track cladding experiments showed that the thermal spraying is the preferred pre-treatment process to achieve defect-free bonding between the CuCrZr alloy and the GH4169 nickel-based high-temperature alloy with a stable melt pool. The GH4169 alloy coating prepared by cold spraying was less effective than that prepared by thermal spraying. The interfaces of single-track deposition after surface modification using PVD, electroplating, and powder spreading processes exhibited defects such as local unmelted areas, microcracks, and poor metallurgical quality.2) The thermal spraying surface modification process on copper substrates can effectively avoid interface defects and forming difficulties under various process conditions, when the surface GH4169 coating thickness reaches 50?150 μm, resulting in metallurgically bonded interfaces. After comparing the main process parameters using a radar chart, a CuCrZr substrate pretreated with a thermal spray coating (thickness of 100 μm) was selected. Using Process 1 to remelt the first layer and Process 2 for deposition, samples with dense metallurgical bonding and good appearance were obtained. Nondestructive testing confirmed that internal defects met the GJB 1580A—2004 (Class AA) requirements.3) The interface region of the prepared CuCrZr/GH4169 dissimilar metals is mainly divided into the CuCrZr alloy substrate, columnar crystal, unmelted powder, Cu element diffusion, and GH4169 alloy zones. The columnar crystal zone is formed by remelting the copper alloy. The unmelted powder zone consists of flaky and spherical particles, mainly from insufficiently melted GH4169 coating and powder. The tensile strength of the CuCrZr/GH4169 dissimilar metals along the deposition direction was 280 MPa±4.24 MPa. The fracture of the tensile samples occurred at the interface, slightly toward the copper alloy side, indicating good bonding at the interface, with the fracture surface confirming ductile fracture.

ObjectiveLaser powder bed fusion (LPBF) is an advanced manufacturing technology that involves the layer-by-layer deposition of metal powder, followed by rapid laser fusion. Unlike traditional methods for metal part fabrication, LPBF which does not require molds or tools can achieve near-net shaping of complex metal part, offering significant advantages. However, commercial LPBF systems generally use low-power (≤500 W), single-mode fiber lasers with Gaussian energy distribution. To fully melt the metal powder layer, key process parameters such as laser scanning speed, spacing, and layer thickness are constrained, resulting in low forming efficiency (1.8?16.2 cm3/h). This limitation hinders the use of LPBF in large-scale manufacturing. To address this, researchers have developed high-power LPBF (HP-LPBF) using lasers with ≥1 kW power. While studies have explored the formation of GH4169 alloys with HP-LPBF, most have used laser powers under 2 kW. Therefore, further investigation is needed to understand the densification behavior, microstructure, and mechanical properties of GH4169 alloys formed with laser powers exceeding 2 kW.MethodsThe HP-SLM320 laser additive manufacturing equipment, used as the HP-LPBF test platform, was developed in-house by our research team. The device was equipped with a multimode fiber laser that had a maximum output power of 4 kW and a near flat-top mode energy distribution. Metallurgical defects in the GH4169 alloys were observed using an optical microscope (OM). Phase composition was analyzed with a X-ray diffractometer (XRD). A scanning electron microscope (SEM) equipped with an electron backscattering diffractometer (EBSD) and an electron probe microanalyzer (EPMA) was used to characterize the microstructure, grain orientation, and composition distribution. Vickers hardness of the vertical section of the specimen was measured using a microhardness tester under a 500 g load and 15 s indentation time. Room temperature tensile tests were conducted on a high-precision electronic universal testing machine at a constant drawing rate of 2 mm/min.Results and DiscussionsIn this study, a high-power, near-flat-top laser beam is used for the HP-LPBF of a GH4169 nickel-based superalloy. The metallurgical defects, microstructure, and mechanical properties of the as-formed HP-LPBF samples are studied. When the laser volumetric energy density is less than 65 J/mm3, unfused defects are observed in the specimens, as shown in Figs. 5(a1)?(c1). However, when the laser volumetric energy density exceeds 65 J/mm3, these defects disappear, and the specimen density exceeds 99.80%. Within the experimental range of this study, the samples prepared with different laser volumetric energy densities exhibit few pores, as shown in Figs. 5 (d1)?(f1). The microstructures of the HP-LPBF samples consist of columnar dendrites and cellular dendrites. Laves phases, which are harmful, are distributed along the dendrite boundaries, similar to what is observed with conventional LPBF technology. However, the primary dendrite arm spacing (PDAS, 1.8 μm) in HP-LPBF specimens is larger than that seen with conventional LPBF (0.5?1.0 μm). Based on the relationship between PDAS and the cooling rate of the molten pool, the average cooling rate in HP-LPBF (9.8×104 K/s) is only 2.0%?16.9% of that (5.8×105?4.8×106 K/s) in conventional LPBF . The average grain size (331 μm) in the HP-LPBF specimen is an order of magnitude larger than that (8.6?32.0 μm) produced by conventional LPBF, as shown in Fig. 9. This is due to the slower cooling rate in HP-LPBF. Additionally, the HP-LPBF specimen exhibits stronger preferred orientation characteristics compared to those produced by conventional LPBF, as shown in Fig. 10, which is attributed to the more uniform temperature gradient achieved with the near-flat-top laser beam.With a density exceeding 99.80%, the forming efficiency (118.8?166.3 cm3/h) of HP-LPBF specimens is more than 7 times that (1.8?16.2 cm3/h) of conventional LPBF technology. The elongation (34%) of a typical HP-LPBF specimen is comparable to the higher range (10%?40%) achieved with conventional LPBF. However, the ultimate tensile strength (895 MPa) falls within the middle to lower range of conventional LPBF results (845?1287 MPa), as shown in Fig. 13. The relatively coarse dendritic structure and relatively slow molten pool cooling rate are the main factors contributing to the elongation being on par with the higher levels observed in conventional LPBF. Meanwhile, the relatively larger solidified grains, coarse dendritic structure, and lower average geometrically necessary dislocation (GND) density are the primary reasons for the ultimate tensile strength aligning with the lower range of conventional LPBF results.ConclusionsSamples with densities exceeding 99.80% can be obtained by adjusting the laser volumetric energy density to ≥65 J/mm3. The as-formed HP-LPBF sample exhibits a dendritic microstructure with a PDAS of 1.8 μm, which is larger than that of the GH4169 superalloy formed using conventional LPBF with a low-power Gaussian laser beam. The Laves phase volume fraction (9.5%) in the HP-LPBF sample is comparable to that obtained with conventional LPBF. The sample also shows a cubic crystallographic texture with a strong “<001> is parallel to the building direction” orientation, stronger than that observed in conventional LPBF. The average equivalent grain size (331 μm) is an order of magnitude larger than in conventional LPBF. The ultimate tensile strength (895 MPa) of the HP-LPBF sample is within the middle to lower range of conventional LPBF results, while its elongation (34%) is on par with the higher range. Additionally, the forming efficiency (118.8?166.3 cm3/h) is more than 7 times that of conventional LPBF, given a density above 99.80%.

ObjectiveLaser powder bed fusion (LPBF) technology can shape metal components into almost any complex shape. Casting is the most commonly used method for fabricating magnesium (Mg) alloy components. However, because of the high vapor pressure and susceptibility of Mg to reacting with air, cast Mg alloys often exhibit defects and relatively poor mechanical properties. Mg alloys manufactured using methods such as forging, rolling, and extrusion are deformed to improve performance; however, forming complex magnesium alloy components is difficult. Although traditional manufacturing methods have laid the foundation for improving Mg alloy properties and their applications, these alloys struggle to meet the demands of complex components in fields such as aerospace, biomedicine, and electronic communication. The application prospects are widened by combining the characteristics of Mg alloys such as high specific strength, high specific stiffness, good electromagnetic shielding performance, and extremely low weight. Currently, the density of Mg alloys formed by LPBF is generally low, and the mechanisms underlying defect formation and microstructural evolution remain unclear. In this study, the densification behavior, defect formation mechanism, and microstructure of LPBF-formed AZ91D magnesium alloy are investigated under different process parameters, and high-quality samples of AZ91D magnesium alloys are formed using LPBF technology.MethodsAZ91D magnesium alloy specimens were formed using LPBF equipment with a fiber laser wavelength of 1064 nm and a maximum laser power of 500 W. During processing, the laser spot size was adjusted to 80 μm, and two preheating temperatures of 25 ℃ and 200 ℃ were applied. Square specimens measuring 10 mm×10 mm×10 mm were formed on cast AZ91D magnesium alloy substrates. An optical microscope (OM) was used to capture metallographic images, and ImagePro Plus software was used for defect shape and type statistics analysis. A scanning electron microscope (SEM) was employed to analyze the internal morphology of the defects and the microstructure of the formed specimens. The elemental composition of the specimens was characterized using a SEM with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscope (EDS). An universal material testing machine was used to conduct room-temperature static tensile tests on relevant specimens.Results and DiscussionsUnder a preheating condition of 200 ℃, the forming interval of AZ91D magnesium alloy can be distinctly divided into porosity, transition, dense forming, and unmelted zones. In the dense forming area, high-density (99.9%) AZ91D specimens without voids or lack-of-fusion defects were successfully formed. Under the processing conditions used in this study, the forming density was sensitive to hatch space such that when the hatch space increased to 0.08 mm, the overall forming density decreased significantly. In Fig. 5, when the hatch space is 0.08 mm, the range of input energy density (150 J/mm3≤ρE≤280 J/mm3) in the dense forming zone decreases significantly compared with that (120 J/mm3≤ρE≤380 J/mm3) when the hatch space is 0.06 mm, and the unmelted range significantly increases. An increase in hatch space leads to more inter-track lack-of-fusion defects, resulting in a larger unmelted zone. Under the preheating condition of 25 ℃, several specimens cannot be formed simultaneously, and the formation is unstable. During the formation of Mg alloys, evaporation of elements leads to a large number of porosity defect variations formed according to the Stokes law in Equation (4). At a high laser power and low scanning speed, keyhole and vapor pores appear simultaneously. In samples with a hatch space of 0.08 mm, unmelted powder is observed in the unmelted zone, presenting a typical inter-track lack-of-fusion shape. At a high laser power and low scanning speed, a large number of elements evaporate during the forming process of magnesium alloys, which removes heat and shields the laser. Under a preheating condition of 200 ℃, the evaporation of elements is the dominant factor affecting the grain size of specimens formed using different parameters. Under the same processing parameters, specimens formed under a preheating temperature of 25 ℃ exhibit finer grains than those formed at 200 ℃, with the cooling rate being the dominant factor. The microstructures of the formed AZ91D magnesium alloy specimens are determined based on the cooling rate and evaporation of the elements. However, under a preheating temperature of 25 ℃, a higher temperature gradient predisposes the specimens to cracking, interfering with their formation.ConclusionsHigh-density specimens (99.9%) were successfully formed without porosity or lack-of-fusion defects under a preheating condition of 200 ℃, with a laser power of 200 W, scanning speeds ranging from 300?400 mm/s, and a hatch space of 0.06 mm. With an increase in hatch space to 0.08 mm, inter-track lack-of-fusion defects increased, leading to a decrease in overall forming density and a reduction in the forming window, as the dense forming input energy density range changed from 120 J/mm3≤ρE≤380 J/mm3 to 150 J/mm3≤ρE≤280 J/mm3. The specimens were characterized by keyholes and evaporative pores with different morphologies on the inner surfaces of their walls. The evolution of the specimen microstructures was jointly determined by the cooling rate and element evaporation. At the same preheating temperature, specimens with severe element evaporation usually had finer grains. For the same processing parameters, the specimens with lower preheating temperatures had finer grains because of the higher cooling rate. With the dense forming parameters, the ultimate tensile strength (UTS) reached (322.04±6.72) MPa, and the yield strength reached (258.07±4.72) MPa, and the mechanical properties far exceeded those of cast Mg alloys, reaching forging standards.

ObjectiveRecent studies have shown that Ti6Al7Nb alloy, which is prepared to improve biocompatibility, exhibits mechanical properties comparable to Ti6Al4V alloy while demonstrating superior corrosion resistance, ductility, biological compatibility, and bioactivity. It is considered an ideal biomaterial for medical titanium alloys. However, for components with complex geometries or medical implants, traditional manufacturing methods require significant time and labor costs. To overcome these manufacturing barriers, the use of laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) technology for producing metal components and implants has emerged as a solution. However, determining the optimal processing window for LPBF is challenging owing to the multiple parameters affecting the quality of the products. Additionally, during the LPBF process, excessive cooling rates can lead to rapid solidification of the melt pool, resulting in the formation of fine grains and supersaturation. In the case of LPBF-formed Ti6Al7Nb alloy, the presence of ultrafine needle-like α' martensitic structures leads to a high yield strength but low ductility because of the formation of α' martensite. While the strength of the material is guaranteed, there may be shortcomings in plasticity. Therefore, post-processing heat treatment of the formed components is essential. This study aims to adjust the key parameters of LPBF to obtain the optimal processing window and conduct heat treatment on specimens formed using the optimal processing parameters. The influence of the main parameters of LPBF on the quality of the formed products is investigated, and the effect of different treatment methods on the microstructure and mechanical properties of the specimens is analyzed.MethodsIn this study, Ti6Al7Nb powder with a particle size distribution of 25?65 μm was used to prepare alloys with different forming parameters. Five sets of parameters for laser power and four sets each for hatch spacing and scanning speed were established, resulting in a total of 80 experiments conducted using an orthogonal experimental design. The optimal processing parameters were determined through a phase analysis of the formed alloys (Fig. 3 and Table 3). Subsequently, the specimens formed using the optimal parameters were subjected to heat treatment using the three solution treatment temperatures shown in Table 2. The microstructure variations were studied via optical microscopy, scanning electron microscopy, and X-ray diffraction analysis. Tensile tests were performed to obtain the mechanical properties of the specimens subjected to different treatments, and fractographic analysis was also conducted. The optimal heat treatment regimen was derived through these methods.Results and DiscussionsIn the LPBF-formed alloy specimens, columnar β-phase crystals grow along the formation direction, whereas needle-like α' martensite phases precipitate at a 45° angle to the formation direction, as illustrated in Fig. 8. The material exhibits high strength but low ductility, with the tensile fracture surface mainly characterized by shallow dimples and transgranular cracking features [Figs. 13(a)?(d)]. This behavior is attributed to the significant differences in thermal gradient present in the LPBF process. Under 850 ℃ solid solution treatment, the strength of the specimens decreases, whereas the ductility significantly improves, surpassing ASTM standards. The tensile fracture surface exhibits pronounced necking, primarily due to the decomposition of the needle-like α' phase into α+β phases during high-temperature heat treatment, although the decomposition is not complete. In contrast, 950 ℃ solution treatment results in the dispersion and pronounced orientation of needle-like α' martensitic phases and an increase in the precipitation of β phases within the grain interiors, with secondary α phases isolated by the organization of the β phase. This structural arrangement leads to lower strength and ductility in the S2 specimen compared to the S1 specimen, albeit with a slight increase in surface hardness. Heat treatment at 1050 ℃ within the α+β dual-phase region results in a typical Widmanst?tten microstructure. The β phase undergoes β→α+α' transformation at high temperatures, leading to a significant increase in material hardness and strength, but with reduced ductility compared to the previous two heat treatments (Figs. 11 and 12). The tensile fracture surfaces display extensive tearing ridges and river-like patterns. After aging treatment, the microstructure of the solid solution treated specimens undergoes minimal change, but both the strength and ductility exhibit improvement, particularly in terms of yield strength. The enhanced strength is attributed to the further decomposition of the metastable α' phase, the increased content of dispersed α+β phases, and the strengthening effects of fine grains, as corroborated by Fig.s 6 and 7. An integrated analysis of the experimental heat treatment regimens indicates that a combination of the 850 ℃×0.5 h / air cooling (solid solution treatment) and 550 ℃×0.5 h /air cooling (aging treatment) can achieve an optimal strength?ductility balance for LPBF-formed Ti6Al7Nb alloy specimens.ConclusionsThe Ti6Al7Nb alloy was successfully shaped using LPBF technology, and by controlling the main forming parameters, the optimal alloy forming quality was achieved. The microstructure and mechanical properties of the alloy were adjusted to meet medical standards through solid solution and aging treatment. The research results indicate that the best formation quality of the specimens is achieved under a laser power of 300 W, a hatch spacing of 0.12 mm, and a scanning speed of 1150 mm/s. The comprehensive results of all heat treatment strategies suggest that a solid solution treatment temperature selected within the mid-section of the α+β dual-phase region is most suitable. At this temperature, the needle-like α' martensitic phase decomposes into the α+β phase and distributes uniformly throughout the alloy. With an increase in the solid solution treatment temperature, although the complete decomposition of the needle-like α' martensitic phase is more pronounced, higher undercooling can lead to the transformation of the β phase into the α and α' phases. Following the aging treatment, the overall strength of the alloy is enhanced owing to the recrystallization and decomposition of the α' phase.

ObjectiveThe laser fabrication of Ti6Al4V (TC4) alloy in an atmospheric environment is susceptible to nitrogen (N) and oxygen (O); consequently, defects such as cracks can occur because of the induced embrittled nitride and oxide phases. Therefore, the industrial application of LDED (laser direct energy deposition) -treated titanium alloy components has been severely hindered by the limited space and high cost in the closed environment. In this study, a novel nozzle with a protective hood was designed for the laser additive manufacturing of TC4 alloys to alleviate the adverse effects of N and O in an atmospheric environment. The microstructures and mechanical properties of the as-deposited TC4 specimens with and without hoods (named TC4-Y and TC4-N, respectively) were evaluated. A functional prototype of the multiflow-path nozzle was developed using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations with species transport and the k?ε gas model. This study significantly benefits the laser fabrication of low-cost and high-performance Ti components in various industrial fields.MethodsGas-atomized TC4 powder with an average size range of 75 μm was employed to fabricate LDED-treated specimens using an FL-1500 1.5 kW fiber laser. The processing parameters were set as follows: laser power, 500 W; scanning speed, 600 mm/min; and powder delivery rate, 4.85 g/min. Both the central and side gases are high-purity Ar (99.99%) and were flowed at a rate of 10 L/min. CFD simulations of the gas flow adjacent to the substrate surface, which was located 2.5 mm away from the nozzle of the air hood, were performed to evaluate the effectiveness of the hood. To investigate the microstructural evolution of the LDED-treated TC4 alloy, the samples were polished and then etched with Kroll's reagent. The phase compositions were determined using a Miniflex600 X-ray diffractometer (XRD). The microstructure was investigated using a MERLIN scanning electron microscope (SEM) operated at an accelerating voltage of 20 kV and a JEOL-2100 transmission electron microscope (TEM) operated at 200 kV. The mechanical properties of the samples were evaluated using an HVS-1000 microhardness tester and a PWS-E100 universal testing machine.Results and DiscussionsThe simulation results indicate that the facet average mass fractions of N2 and O2 reduced significantly from 1.628×10-3 to 2×10-4 and from 4.37×10-4 to 5.4×10-5, respectively (Fig. 3), which agree well with the experimental results. The TC4-N specimen is composed of needle-like α′ martensite, Widmanst?tten α-laths, β-phase, and nitrides (Figs. 6?8). By applying the protective hood, the TC4-Y specimen exhibits a decrease in α/α′ martensite content, an increase in the β-phase fraction, and the precipitation of Ti3AlC2 phase (Figs. 6?8). The average microhardness values of the TC4-N and TC4-Y specimens are 410 HVand 365 HV(Fig. 4), respectively. The higher microhardness of the TC4-N specimen is primarily due to the in-situ formation of hard nitride TiN (2900 HV) during LDED. In comparison, the TC4-Y samples indicate a slightly lower value (365 HV) that is equivalent to those fabricated in a chamber filled with an inert gas (316?369 HV). Under the protection of the hood, the TC4-Y samples exhibit an average UTS of 1037 MPa, a YS of 952 MPa, and an EL of 10.2% (Fig. 5), which are comparable to those of TC4 counterparts achieved in a closed environment. This demonstrates the effectiveness and feasibility of the protective hood.ConclusionsThe newly designed protective hood effectively eliminates the adverse effects of N and O. A CFD simulation was conducted, which demonstrated that the hood successfully prevented contamination by impurities, including N and O. The N and O mass fraction adjacent to the sample surface decreased by 1.38×10-3 and 5.7×10-4, respectively. The TC4-N specimen is composed of needle-like α′ martensite, Widmanstatten α-laths, β-phase, and nitrides. The TC4-Y specimen primarily comprises coarsened α′ martensite, Widmanstatten α-laths, Ti3AlC2 nanoprecipitates, and β-phase. Under the synergistic effect of refinement strengthening, solid-solution strengthening, and second-phase strengthening, the TC4-N specimen exhibits higher levels of strength (UTS of 1249 MPa, YS of 1028 MPa) and microhardness (410 HV). By contrast, an exceptional combination of high strength (UTS of 1037 MPa, YS of 952 MPa) and high ductility (10.2%) is achieved owing to the presence of α/α′ with a low aspect ratio, a high fraction of β-phase, and Ti3AlC2 nanoprecipitates in the TC4-Y specimen. This study reports a simple yet effective approach for producing LDEDed TC4 alloys with outstanding mechanical properties in an atmosphere, which significantly benefits industrial applications.

ObjectiveAs a low-expansion alloy, Invar 36 alloy is commonly used in scenarios involving significant environmental temperature changes and high-precision requirements. However, its high density and machining difficulty limit its application in the aerospace field. The use of the laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) technology to fabricate lattice-filled Invar 36 alloy structures can effectively address these issues. Existing studies pertaining to the mechanical properties of lattice-filled structures focus on energy-absorption characteristics under compressive loading. Meanwhile, studies regarding the optimization of the structural stiffness of lattice-filled structures under compressive loading are scarce. Therefore, lightweight and high-stiffness lattice-filled structures must be urgently developed. Additionally, studies regarding lattice-filled structures based on Invar 36 alloy have not yet been reported. This study uses LPBF technology to fabricate Invar 36 alloy lattice-filled structures with various structural parameters, which results in good forming performance. Furthermore, this study provides valuable insights into the lightweight design of Invar 36 alloy components.MethodsInvar 36 alloy lattice-filled structures with different structural parameters were fabricated via LPBF. The strut diameters are 0.8, 1.0, and 1.2 mm; the cell dimensions are 4, 6, and 8 mm; and the thickness of the skin is 1 mm. Optimized fabricating parameters were used: laser power, 280 W; scanning spacing, 0.12 mm; scanning speed, 1200 mm/s; powder thickness, 0.04 mm; and interlayer turn angle, 67°. A strip-scanning strategy featuring a strip width of 7 mm and a strip overlap of 0.08 mm was adopted. After fabrication, the samples were heat treated by increasing the temperature to 750 ℃ and maintaining it for 1.5 h, followed by cooling down to room temperature under argon atmosphere. The samples were sandblasted and cleaned ultrasonically to remove adhesive powder from the sample surfaces. Quasi-static compression tests and finite-element analyses were performed on the lattice-filled structures to investigate and analyze the compression curves, deformation modes, and stress distributions.Results and DiscussionsThe compression stress?strain curves of the lattice-filled structures with different structural parameters are shown in Fig. 5. For the lattice-filled structures with cell dimensions of 8 mm and 6 mm, the curves can be classified into four characteristic regions: the elastic region; the force-drop region featuring a significant decrease in compressive stress; the plateau region; and the densification region. By contrast, the lattice-filled structure with cell dimensions of 4 mm neither exhibits a peak nor a compressive-stress-decrease region, which can be classified into three regions. This difference is primarily related to the deformation mode of the lattice-filled structures. When the strut diameter and number of lattice layers are small, the compressive deformations of the lattice-filled structures are primarily determined by the behavior of the lateral skin, which results in deformation characterized by skin wrinkling and shear-type global buckling (Fig. 7). Under these deformation modes, the compression curve is reflected by the abrupt stress after the peak strength. The compression performance of the lattice-filled structure is significantly enhanced when the strut diameter and number of lattice layers are further increased. Under this condition, the stronger constraining effect between the skin and lattice core restricts the local buckling of the skin (Fig. 8). However, a larger strut diameter can facilitate load transfer (Fig. 10). The stress is uniformly distributed inside the lattice core, and the local buckling deformation does not cause the compressive stress to decrease abruptly.The Gibson?Ashby model was used to predict the performance of the Invar 36 alloy lattice-filled structures. The higher the relative density, the better is the structural compression (Fig. 11). However, for a specified mass, if the cell dimensions increases, then the strut diameter decreases. Therefore, the coupling effects of the structural parameters must be considered when designing lightweight materials.ConclusionsThe effects of structural parameters on the compression performance and deformation behavior of Invar 36 alloy lattice-filled structures were investigated via quasi-static compression tests and finite-element analyses. First, the compressive elastic modulus, plateau stress, and energy-absorbing properties of the lattice-filled structures fabricated via LPBF improve significantly as the cell dimensions decreases and the strut diameter increases. Second, the lattice-filled structures with different structural parameters exhibit three deformation modes: skin wrinkling, shear-type global buckling, and local skin buckling. Their deformation behaviors are coupled with skin tensile-dominated and lattice-filled core bending-dominated deformations. Third, the deformation behaviors obtained from finite-element analysis are consistent with the compression test results. Moreover, different structural parameters significantly affect the load transfer and stress distribution, which ultimately results in lattice-filled structures exhibiting different deformation modes. Finally, the coupling effect of the structural parameters should be fully considered when using lattice-filled structures as lightweight Invar 36 alloy members. For a specified mass, a cell dimension of 6 mm and a strut diameter of 1 mm are the better parameters for optimizing the structural stiffness, which can yield 1.75 GPa·g-1·cm-3 for the latter.

ObjectiveTitanium alloys are widely used in aerospace, automotive manufacturing, and marine engineering because of their high strength, low density, and excellent corrosion resistance. Laser welding, owing to its high energy density, high precision, and small heat-affected zone, provides robust support for connecting critical titanium-alloy components in industrial applications. However, during the laser welding of titanium alloys, the involved high-density Gaussian laser energy can generate defects easily, e.g., pores in the weld seam, thus adversely affecting the performance of the welded joint. In laser manufacturing, the emergence of novel lasers offers new possibilities for suppressing such defects. Fiber-diode laser hybrid welding enables the efficient and high-quality welding of highly reflective materials and has garnered widespread attention from academia and industry. Nevertheless, the effects of diode laser power and welding speed on titanium-alloy welding properties in fiber-diode laser hybrid welding remain unclear, thereby hindering theoretical guidance and process optimization for industrial applications. Therefore, this study investigates the effects of diode laser power and welding speed on the formation, microstructure, and mechanical properties of joints realized via fiber-diode laser hybrid welding to determine the optimal process window.MethodsIn this study, the effects of diode laser power (1.0, 1.5, and 3.0 kW) and welding speed (30, 60, and 120 mm/s) on the formation, microstructure, and mechanical properties of 4 mm thick TC4 titanium-alloy joints welded via fiber-diode laser hybrid welding were investigated. Welding experiments were performed using a fiber laser with a wavelength of 1080 nm, a core diameter of 34 μm, and a spot diameter of 45 μm, and a diode laser with a wavelength of 915 nm, a core diameter of 600 μm, and a spot diameter of 1.2 mm. High-purity (volume fraction of 99.99%) Ar gas flowed at a rate of 30 L/min was used as the shielding gas during welding. The experimental parameters are listed in Table 2.Results and DiscussionsFigure 2 shows the macrosectional formations of the welds at different diode laser powers. As the diode laser power increases, the weld morphology transforms from a “Y” shape to a “goblet” shape, with the upper weld width increasing by approximately 60% (from 1.8 mm to 2.9 mm). Simultaneously, the width of the heat-affected zone increases, whereas that of the lower weld remains relatively unchanged. This indicates that the diode laser energy preferentially conducts heat laterally, thereby modulating the transient thermal convection within the molten pool. As depicted in Fig. 3, the grains in the hybrid-laser action zone are much coarser compared with those in the single-laser action zone, which is attributable to the higher heat input. In terms of the mechanical properties, as shown in Fig. 4, the tensile strength decreases with increasing diode laser power (from 918 MPa to 907 MPa), whereas the elongation after fracture remains relatively constant (average of approximately 6%), with fracture occurring in the weld seam. The fracture morphology shows an increase in the number of keyhole-type pores in the weld as the diode laser power increases. This suggests that excessive diode laser power destabilizes the keyhole, thus deteriorating the mechanical properties of the joint.Figure 6 shows the macrosectional formations of the welds at different welding speeds. As the welding speed increases, the weld formation changes from an “X” shape to a “Y” shape, and the width of the heat-affected zone decreases due to reduced heat input. As shown in Fig. 7, the grain size decreases with increasing welding speed (from 2.99 μm to 2.87 μm). This reduction in grain size causes an increase in the number of grains and thus an increase in the proportion of high-angle grain boundaries (from 80.5% to 84.0%). In terms of the mechanical properties, as illustrated in Fig. 10, both the tensile strength and elongation after the fracture of the joints first increase and then decrease with increasing welding speed, with the maximum tensile strength reaching 927 MPa and the elongation being 9%. Fractures occur in the base material. As shown in Fig. 11, an increase in the welding speed reduces the heat input, refines the grain size, and enhances the mechanical properties of the joint. However, when the welding speed further increases to 120 mm/s, the solidification rate of the molten pool decreases significantly, thus preventing bubbles from escaping and deteriorating the mechanical properties of the joint.ConclusionsDuring laser hybrid welding, the energy of the diode laser tends to propagate laterally, which is conducive to stabilizing the keyhole and reducing the porosity in the weld seam. However, when the power of the diode laser exceeds a certain range, an increase in the laser power can paradoxically reduce the stability of the optically induced keyhole, thus deteriorating the mechanical properties of the joint. As the welding speed increases, the heat input decreases, thus refining the grain size considerably and increasing the number of high-angle grain boundaries. Nevertheless, the values of the mechanical properties first increase and then decrease as the welding speed increases. This is because, when the welding speed exceeds a certain threshold, the solidification time of the molten pool shortens, thus preventing bubbles from escaping in time. Consequently, the porosity of the weld seam increases and the mechanical properties of the joint deteriorates.

ObjectiveLaser-powder-filling welding is an important method for joining aluminum matrix composites owing to its high processing speed, minimal thermal impact on the matrix, and excellent controllability. However, in practical applications of laser-powder-filling welding, the intense Marangoni convection in the aluminum-alloy molten pool results in undesired weld morphologies such as humps and surface instability, thus deteriorating the mechanical properties and stability of the joints. Magnetic-assistance technology, owing to its advantages of high flexibility, high efficiency, low cost, and non-contact nature, has become a potentially effective method to control the flow of molten metals, improve welding controllability, and enhance product quality. Recent studies that improve welding quality using steady magnetic fields primarily focus on the effect of magnetic fields on arc welding or deep-penetration laser welding. Meanwhile, most studies examine the effects of transverse steady magnetic fields on aluminum-alloy welding, whereas few studies investigate the powder or wire-filling welding of aluminum matrix composites. Thus, the effect of reinforcements on the physical properties of the base metal is yet to be elucidated. Furthermore, owing to the difficulty in capturing the flow behavior of molten pools and the complex effect of external magnetic fields in the molten pool, the mechanisms of magnetic-field distributions and the Lorentz force in the molten-pool flow field under magnetic-field assistance remain ambiguous. Therefore, welding simulation studies should be conducted on magnetic-field-assisted aluminum matrix composites.MethodsA SiCp/2009Al composite matrix and AlSi12 filler powder are used in this study, with the magnetic field directed vertically perpendicular to the bottom surface of the matrix, and the magnetic-field intensity reaching 1.0 T. First, a three-dimensional transient numerical model is established using the COMSOL Multiphysics simulation software, which considers the variations in the material physical properties and couples fluid heat transfer with the magnetic field. Meanwhile, thermal buoyancy, surface tension, the Lorentz force, and other forces are applied to the molten pool. Subsequently, the Lorentz-force distribution in the steady magnetic field, as well as the fluid flow, heat transfer, and cooling behaviors in the central region of the molten pool are investigated. Finally, the profile morphology of the molten pool is verified through experimental observations.Results and DiscussionsThe functional relationship between the longitudinal section height of the weld and the magnetic flux density was obtained via fitting, which provides clear understanding regarding the decay law of the magnetic field in space. Under the action of the longitudinal magnetic field, the molten pool is primarily affected by transverse electromagnetic forces, which can generate a shear effect on the interface (Fig. 4). As the steady magnetic flux density increases, the Marangoni convective motion in the molten pool weakens gradually, whereas the vortex rings on the front and rear sides of the molten-pool center diminish gradually until they disappear, thus decreasing the convective heat-transfer intensity in the molten pool, reducing the temperature gradients, and resulting in a more uniform distribution of the laser heat input in the longitudinal direction (Figs. 5, 6, and 7). Additionally, the cooling rate in the molten pool decreases significantly with the magnetic flux density, and the cooling and heat dissipation mechanisms of the molten material primarily involve thermal conduction and radiative heat loss (Fig. 8). At any position of the molten pool in the steady magnetic field, the induced Lorentz force and convective flow are in opposite directions, thus compensating for the Marangoni shear force and yielding an electromagnetic braking effect on the molten pool, which is the primary contributor to the weakening of convective heat transfer in the molten pool (Figs. 9 and 10). Meanwhile, the simulated molten-pool contour undulation and the mushy zone decrease. Additionally, a uniform microstructure distribution, good formability, and welding joints with reduced porosity are achieved from the welding processes (Fig. 11). The simulation results of temperature-field distribution and geometry agree well with the experimental results.ConclusionsIn the laser-powder-filling welding of SiCp/2009Al composites under the assistance of a steady magnetic field, the magnetic field alters the energy distribution in the molten pool, which minimizes the thermal gradients and consequently reduces the heat-affected zone of the welding joint, thus resulting in a more uniform microstructure distribution. Meanwhile, the steady magnetic field reduces the cooling rate of the molten pool, favors an extended period for allowing bubbles to escape the solidification interface, and decreases the number of pores in the welded joint. Increasing the magnetic flux density will further weaken the Marangoni convection in the molten pool and reduce the heat-transfer intensity of convection in the molten pool. The convective vortices gradually diminish until they disappear, thus resulting in a more stable flow in the molten pool. Furthermore, the transverse Lorentz force generated by the longitudinal magnetic field exerts a significant braking effect on the lateral fluid flow in the molten pool, thus reducing the cross-sectional size of the molten pool. Solutes are primarily transported toward the bottom of the molten pool under the action of natural convection, thereby improving weld formation.

Objective3D printing of structural electronics can realize the synchronous forming of dielectric substrates and conductive circuits, and it has a broad application prospect in the manufacturing of, for example, flexible wearable and smart skins. The morphology and electrical properties of conductive circuits after sintering directly influence the in-service performance of structural electronic products. The conventional thermal sintering of conductive silver paste circuits usually requires a long period of high-temperature heating, which has a significant impact on the polymer substrate for conductive circuits and reduces their printing accuracy. Although the emerging electric sintering/laser sintering can reduce the thermal impact on the polymer substrate material, the sintered circuits still suffer from internal pores, poor structural shape consistency, and high resistivity. In this paper, we propose a “hot airflow + laser” composite sintering method, which results in sintered circuits with high densities, high consistency, and low resistivity. We hope that this composite sintering method will contribute to the fabrication of higher precision, lower resistivity conductive circuits and help to understand the relationship between sintering temperature and resistivity of conductive silver paste circuits.MethodsThe existing laser sintered conductive silver paste lines suffer from internal pores, circuit expansion, resistivity, and other issues. This study proposes a composite sintering system. A comparison test with single laser sintering is carried out. The surface morphology and internal defects of the sintered circuits are detected. Analyses of conductivity of the silver paste lines, their expansion behavior, and the elemental changes are conducted, showing a clear mechanism of inhibition of the pore defects. A test of the resistance of the circuit is performed to analyze the pattern of change of the resistance value. On this basis, the correlation among pore defects, circuit expansion, and electrical properties is established. This study provides a new method for high density, low resistivity forming of conductive silver paste lines.Results and DiscussionsIn the present study, a “hot airflow + laser” composite sintering process of conductive silver paste is proposed, and a sintering system with hot airflow pre-sintering function is built (Fig. 4). Comparison experiments of laser/composite sintering with variable parameters are carried out (Table 3). The results show that, compared with the laser sintered circuits, the proposed composite sintering leads to lower electrical resistivity (Fig. 6), smaller cross-sectional area (Fig. 9), lower electrical resistance value (Fig. 15), and higher consistency (Fig. 8). The reason for the inhibition of pore defects using the composite sintering process is identified. The hot gas flow promotes the thermal decomposition process of organic substances in the silver paste and volatilizes them from the surface of the nondense silver paste. This avoids the gas volatilization from the dense surface of the laser sintered surface, thus reducing the generation of internal pore defects (Fig. 12). The composite sintering process promotes the reduction in resistance value due to the elevated silver content on the surface of the circuits after hot gas flow sintering, the increase in thickness of the dense surface layer after laser sintering, the increase in the effective transmission area of electrons, and the improvement of the electron flow efficiency (Fig. 17). Finally, the study reveals that the hot airflow promotes the decomposition of organic matter within the silver paste (Table 4), and the laser accelerates the fusion of silver nanoparticles (Fig. 18).ConclusionsThis study proposes a “hot airflow + laser” composite sintering process of conductive silver paste, builds a sintering system with hot airflow pre-sintering function, and carries out a laser sintering and “hot airflow + laser” sintering comparative process test. The low-temperature pre-sintering of the circuit inhibits the internal pore defects, and the electrical properties of the circuit are improved. Based on the characteristics of the organic matter ladder of thermal reaction, it is revealed that the pre-sintering temperature promotes the removal of organic material. A correlation between the organic matter residue and the generation of pore defects is established. This study provides a theoretical basis for the high-precision, low-resistivity molding of conductive silver paste. The specific conclusions are as follows:1) The reduction in resistivity of the conductive silver paste circuit after the “hot airflow + laser” composite sintering, compared with that obtained with laser sintering, is significant. A maximum resistivity reduction of 67% is achieved.2) Hot airflow pre-sintering before laser sintering can promote the decomposition of organic solvents within the conductive silver paste. This avoids the violent reaction produced by laser sintering of organic substances, inhibits the generation of pore defects in the conductive silver paste lines, and reduces the expansion of the conductive silver paste circuits. Compared with that obtained with laser sintering, the circuit cross-sectional area is reduced by 50%?60%.3) “Hot airflow + laser” composite sintering improves the circuit surface layer density, increases the effective cross-section of the circuit current transmission, and reduces the circuit resistance value. Compared with that obtained with laser sintering, the circuit resistance value is reduced by 30%?45%.

ObjectiveMedium-thick aluminum alloys have a wide range of application prospects in railway transportation; therefore, studying the welding of medium-thick aluminum alloys is crucial. Laser-MIG hybrid welding (MIG, metal-inert gas) combines the advantages of laser heat source and arc heat source while compensating for their individual shortcomings, making it particularly suitable for welding medium-thick plates. To enhance welding efficiency, it is essential to analyze the single-layer, single-pass welding process. This study focuses on the microstructures and mechanical properties of laser MIG-welded joints of 6005A aluminum alloys with different groove dimensions.MethodsIn this study, a 10 mm thick 6005A aluminum alloy is welded using the laser-MIG hybrid welding technique in a single-layer, single-pass manner. Welding tests are conducted under a constant laser power, welding speed, and wire feeding speed of 5000 W, 16 m/min, and 8 mm/s, respectively, using different groove dimensions, including a root thickness of 5 mm with groove angles of 50°, 60°, and 70° and a groove angle of 60° with root thicknesses of 4 mm and 6 mm. The microstructures of the welded joints are analyzed using optical microscope (OM) and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD). Tensile tests are performed on the specimens at a rate of 2 mm/min, and the tensile fracture morphology is observed using scanning electron microscope (SEM). The hardnesses of the welded joints are measured using a Vickers hardness tester. Finally, the weld temperature field is investigated using finite element analysis, and time?temperature profiles are extracted for specific locations.Results and DiscussionsA metallographic analysis reveals that successful weld connections are achieved for plates with different groove dimensions under constant processing conditions. Because of the similar heat input during welding, the microstructure of the welded joint exhibits the analogous performance. The grains in the center of the weld zone (WZ) are equiaxed dendrites, whereas those near the fusion zone are columnar dendrites, oriented perpendicular to a fusion line. The heat-affected zone (HAZ) shows randomly distributed, large black precipitate phases, which are significantly larger than the uniformly distributed point-like precipitate phases in the base metal (BM). The grain diameter in the WZ is about 140 μm, while the grain diameters in the HAZ and BM are 73 μm and 76 μm, respectively. The grain diameter in the WZ is much larger than those in the HAZ and BM, whereas the grain diameter in the HAZ is similar to that in the BM (Fig. 7). The tensile strengths of the specimens with different groove dimensions are 75%?79% of that of the BM, indicating that the welded joints have good bond strengths (Table 4). Because all the tensile fractures are in the HAZ, the HAZ is the weakest region (Fig. 8). This is mainly because of the severe softening behavior that occurs in the HAZ during welding. Fracture morphologies indicate that the fracture type is ductile (Fig. 9). The hardnesses of the welded joint in the HAZ and WZ are significantly lower than that of the BM, with the minimum hardness observed in the HAZ (Fig. 10). This reduction is mainly due to the transformation of a strengthening β phase into a β '' phase during thermal cycling. A finite element analysis shows that the region with a peak temperature of 480 °C in the HAZ corresponds to the location of minimum hardness (Fig. 13).ConclusionsThe paper studies the single-layer, single-pass laser-MIG hybrid welding process of a 6005A aluminum alloy with a thickness of 10 mm, and the relevant properties of the welded joints with different groove dimensions are analyzed. Plates with different groove dimensions are successfully joined at a laser power of 5000 W, wire feed rate of 16 m/min, and welding speed of 8 mm/s. The grains in the WZ are equiaxed at the center and columnar at the fusion line. The material in the WZ undergoes repetitive melting and solidification to form larger grains, whereas the grains in the HAZ and BM remain almost unchanged. The HAZ is the weakest region of the welded joints of the aluminum alloy 6005A. The tensile properties of specimens with different groove dimensions are similar, and their fracture characteristics are mainly ductile. Softening behavior occurs in all the welded joints, and the heat-affected zone exhibits minimum hardness. An analysis of the corresponding welding temperature field confirms that the region with a peak temperature of 480 °C is the softest region of the welded joints.

ObjectiveIn the field of electronic packaging, the preparation and application of traditional electronic packaging materials such as W/Cu and Mo/Cu are relatively mature. However, these materials have high density and low thermal conductivity, which cannot meet the packaging requirements of high-power portable electronic devices. Aluminum matrix composites have higher strength, wear resistance, and economy, which not only can overcome the shortcomings of traditional packaging materials but can also meet the application requirements of electronic packaging. In SiCp/Al composites, SiC particles react with the Al matrix to form needle-like brittle phase Al4C3 during high-temperature melting, which diminishes the welding performance of the joint and severely restricts the welding application of the material. Swing laser welding is expected to improve the microstructures and performances of SiCp/Al welded joints by improving the weld-forming morphology and inhibiting pore formation. Few studies have been conducted on the effects of the beam swing on the laser welding of SiCp/Al composites. Accordingly, in this study, the effects of beam swing mode, amplitude, and frequency on the laser welding of SiCp/Al composites were systematically analyzed. The effects of different laser swing modes and process parameters on the laser welding of SiCp/Al composites are revealed by controlling the variable method. The study on the welding microstructure and mechanical properties provides valuable experimental data for obtaining effective welding of SiCp/Al composites.MethodsThe test materials were a welding wire with a diameter of 1.2 mm and a SiCp/6005A composite material with dimensions of 60 mm×50 mm×4 mm. The effects of the different swing parameters on the welding properties of the SiC/Al composites were studied using the control-variable method (Table 2). Four modes of laser beam swing were used during welding: Linear, Circular, “8,” and Infinite (Fig. 2). The swing laser welding process parameters were as follows: laser power of 7500 W, defocusing amount of 0 mm; wire feeding speed of 5 m/min, welding speed of 4.2 m/min, and gas flow rate of 15 L/min. Following welding, the weld morphology and microstructure were observed using optical microscope (OM) and scanning electron microscope (SEM). A tensile test was conducted using a universal testing machine. Micro-Vickers hardness was used for the hardness test. We analyzed the effects of the laser oscillation parameters on the weld in terms of the weld morphology, phase structure distribution, yield strength, and hardness distribution of the sample.Results and DiscussionsResults show that the linear weld formation has a shorter swing path, smaller spot area, more concentrated laser energy density, more continuous weld formation, and more rounded and uniform front and back weld formation. When no swing is applied (swing amplitude of 0 mm), the upper surface of the weld is not flat, and undercutting occurs. When the swing amplitude is increased, the molten pool is heated more evenly, enabling more stable solidification, which in turn reduces the surface roughness (Figs. 3?5). Under different swing modes, the action time of the laser on the molten pool is different, which increases the time required for the SiC reaction to form Al4C3. The higher the frequency of the laser oscillation, the shorter is the action time of the laser in the width direction of the weld, and the shorter is the time of the SiC reaction to form Al4C3. Therefore, when the swing frequency is 50 Hz, the SiC content is the highest. The effects of different swing amplitudes on the SiC content in the weld are comprehensive. When the swing amplitude is large, the heating area is large, and more Al4C3 is formed by the SiC reaction, the lower is the energy density, the more Al4C3 is formed by the SiC reaction, and the small swing amplitude group is the opposite (Fig. 7). In general, swing welding is beneficial for refining weld grains. However, an excessively complex swing mode increases the time required for the SiC reaction to form Al4C3, thereby reducing the mechanical properties of the welded joint. The fine-grain strengthening effect fails to compensate the strength-weakening effect caused by the Al4C3 phase (Fig. 8). When the tensile specimen breaks, the specimen fractures along the weld center enriched by the needle-like brittle phase Al4C3. During the tensile process, the pores in the weld are enlarged, and the cracks also extend along the Al4C3-enriched area. Al4C3 exhibits a weak bond with the aluminum matrix. During the tensile process, the aluminum matrix with better toughness is first stretched, and the shedding of the needle-like brittle phase Al4C3 causes the original position of Al4C3 to become the beginning position of the crack. Therefore, it cracks along the weld center enriched by the needle-like brittle phase Al4C3 (Fig. 10).ConclusionsAppropriate swing parameters can inhibit the formation of Al4C3 from SiC, effectively inhibit pores, obtain a good weld surface and uniform weld structure, achieve a certain tensile strength, and provide good mechanical properties. However, an excessive swing increases the time and range of heat input, promotes the formation of Al4C3 from SiC, and weakens its mechanical properties. Thus, good swing parameters are obtained, namely, a 50 Hz swing frequency and 1 mm swing amplitude in linear swing mode.

ObjectiveBoth 2060-T8 and 2099-T83 are new third-generation aluminum-lithium (Al-Li) alloys that have been applied in the aviation industry. These two types of Al-Li alloys have excellent specific strength, elastic modulus, and fatigue resistance. Owing to the addition of lithium in the alloy, the structural weight can be further reduced by 10%?15%. Compared with conventional aluminum alloys used in aviation, however, laser-welded Al-Li alloys are more likely to form hot cracks and pores. In addition to welding parameters, changes in weld composition are closely related to the formation of hot cracks and pores. In particular, the composition and precipitation phase of weld grain boundaries are closely related to the formation of hot cracks. When welding wires with high Si content such as ER4047 are used, Al2Cu, LiAlSi, and Al-Si divorced eutectics are primarily formed at the grain boundaries. However, studies showed that 4047 welding wires cannot completely suppress the generation of hot cracks. By contrast, an excessively grown LiAlSi phase will deteriorate the grain-boundary performance. In this study, for the double-sided laser-beam welding of Al-Li alloy T-joints, we use five types of welding wires with different Si and Cu contents. Thus, the grain-boundary microstructure is effectively controlled by the composition of the welding wire. Hot cracks and porosity defects in the weld are suppressed effectively. Additionally, the transverse tensile and longitudinal compression properties of the T-joints improve significantly. This study may serve as a reference for the engineering application of double-sided laser-beam welded 2060/2099 Al-Li alloy T-joints.MethodsIn this study, 2-mm-thick 2060-T8 and 2099-T83 Al-Li alloys are used. Optimized parameters are used for the double-sided laser-beam welding of Al-Li alloy T-joints. The double-sided laser-beam-welding system platform comprises two fiber lasers and two wire feeders controlled by two 6-axis industrial robots. The fiber lasers, which feature an emission wavelength of 1.07 μm, can be delivered in the continuous wave (CW) mode. The laser beam passes through a focusing mirror with a focus length of 192 mm and is finally focused as a spot measuring 0.26 mm in diameter. The optimized mixing parameters are as follows: laser wavelength, 1.07 μm; laser power, 3000 W; laser scanning speed, 10.0 m·min-1; wire-feeding speed, 4.3 m·min-1; wire extension, 8.0 mm; and shielding-argon-gas flow rate, 15.0·L·min-1. No heat treatment is performed on the welded T-joints post welding. Five types of welding wires with different Si and Cu contents are evaluated for the grain-boundary alloy regulation of the double-sided laser-beam welded Al-Li alloy T-joints. Prior to analysis and testing, the surface of the T-joint weld is first treated with Keller reagent for corrosion. The macrostructure characteristics of the weld are observed using an optical microscope (OM). The microstructure characteristics of the weld are observed using scanning electron microscope (SEM). The transverse tensile and longitudinal compression performances of the T-joints are evaluated.Results and DiscussionsBased on SEM observation, the T-joint weld comprises columnar dendrites, equiaxed dendrites, and an equiaxed grain zone (EQZ), whereas the weld grain boundary primarily comprises Al2Cu, LiAlSi, and Al-Si divorced eutectics. When the Si mass fraction is extremely low (4.18%) in wire 1# or extremely high (7.23%) in wire 3#, cracks distributed along the transverse and longitudinal directions are observed in the T-joint welds. Meanwhile, when the Cu mass fraction (7.13%) in the wire is extremely high, crack and porosity defects are observed in the welds (Fig. 5). The cracks and pores are located in the columnar- and equiaxed-dendrite zones, and the cracks are formed along the grain boundaries (Fig. 6). When the Si and Cu mass fractions in wire 4# are 5.41% and 6.17%, respectively, Al2Cu fully precipitates and presents a grid-like distribution at the grain boundaries, whereas LiAlSi maintains a small size of less than 1 μm. However, further increasing the Si and Cu contents in wire 5# disrupts the grid distribution of Al2Cu and significantly expands the LiAlSi phases, thus causing cracks and porosity defects to reappear (Fig. 7). The mechanical properties of the T-joints are closely related to the microstructure and defects of the weld. When using wire 4#, the T-joints achieve a maximum average transverse tensile strength of 406 MPa and a maximum average longitudinal compressive load of 95 kN (Figs. 8 and 9).ConclusionsWhen using Si-Cu wires for welding, the double-sided laser-beam welded Al-Li alloy T-joints comprise an EQZ adjacent to the fusion line, a columnar-dendrite zone adjacent to the weld surface and EQZ, and an equiaxed dendrite zone at the center of the weld. The weld grain boundaries primarily comprise an θ phase (Al2Cu), a T phase (LiAlSi), and Al-Si divorced eutectics. The different Si and Cu contents in the welding wire affect the formations and microstructures of the θ phase, T phase, and Al-Si divorced eutectics. Excessively low or high Si and Cu contents can result in the formation of hot cracks along the grain boundaries in the columnar- and equiaxed-dendrite zones. When the Si and Cu mass fractions in the welding wire are 5.41% and 6.17%, respectively, the θ phase on the weld grain boundary is distributed in a grid-like manner and the T-phase size is controlled below 1 μm, which resultes in a significant second phase-strengthening effect. Furthermore, the cavities formed by the solidification shrinkage of the intergranular liquid phase can be filled and repaired by the Al-Si divorced eutectics, thereby suppressing hot cracks and porosity defects. When the Si and Cu mass fractions in the welding wire are 5.41% and 6.17%, respectively, the maximum average transverse tensile strength of the T-joints is 406 MPa, which is 80% of the skin tensile strength. The maximum average longitudinal compressive load of the T-joints is 95 kN. These test results based on the optimal composition of wire 4# are the best among the five tested wires.

ObjectiveTa-10W with a high melting point of 3035 ℃, exhibits good mechanical properties at high temperatures, good thermal shock resistance, and a small coefficient of linear expansion. GH3128 is a single-phase high-temperature austenitic alloy with W and Mo as solid solution elements developed in China, resistant to corrosion and oxidation, with excellent creep durability and weldability. GH3128 is now being widely used in engine combustion chambers, air intakes, tail nozzles, radiators, and other components with density and cost lower than those of Ta-10W. In aero-engine manufacturing, the high-performance welding of Ta-10W with GH3128 not only significantly reduces the weight of the engine but also improves the engine thrust-to-weight ratio. In addition, engine manufacturing costs are significantly reduced while meeting the thermal service requirements of the engine at different locations. Welding Ta-10W with GH3128 combines the advantages of the two materials, allowing the exploration of useful methods for the manufacturing of key components in aero-engine high-temperature services.MethodsThe experimental material consisted of 25 mm×50 mm×3 mm GH3128 and Ta-10W plates. The welding light source was a fiber laser with a rated output power of 6000 W and a wavelength of 1060?1070 nm. A five-axis machine tool was used as the motion control system, and the positioning accuracy was 0.02 mm. The experimental diagram is shown in Fig. 1(a). Using the self-developed Ta-10W welding protection nozzle and high-purity argon (volume fraction of 99.999%) as the protective gas, the back protection device protects the back of the weld. The flow rate of the protection nozzle was 8 L/min, and the flow rate of the back was 8 L/min. Before welding, acetone was used to clean and ensure that the weld specimen had no wrong edges and no gaps in the interface. In the process experiments, initially, welding speed of 2 m/s, laser powers of 2500, 2750, and 3000 W, and defocusing amount of0 mm were used. The laser power was increased to 5000 , 5500 , and 6000 W, and the welding speed was increased to 5 m/min and 5.5 m/min. Finally, welding experiments with offsets of -0.2, 0.2, and 0.4 mm were performed under process parameters of 5500 W and 5 m/min. After welding, the front and back molding of the weld was observed using a super depth-of-field microscope. The sampling method is shown in Fig. 1(b). The welded specimens were cut into 10 mm×10 mm×3 mm block specimens using wire-cutting, and the metallographic specimens were prepared using the epoxy resin inlay method [Fig. 1(b)]. After sequential grinding and polishing with water-abrasive sandpaper, the welds were corroded using HCl and HNO3 at a volume ratio of 3∶1 for 15?20 s. The cross-sectional morphologies of the welds and their microstructures were photographed using a super depth-of-field microscope. The microstructure of the weld was further observed using a scanning electron microscope and its accompanying energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) inspection equipment, to detect the physical phase of the weld. In the mechanical properties section, hardness tests were performed at 150 μm intervals using a Vickers hardness tester with a load of 200 g and a holding time of 15 s. The test area included the base material Ta-10W, GH3128, and the welds. In the tensile strength section, the room temperature mechanical properties of the joints were tested using a tensile testing machine. Considering the requirements of the testing equipment, small-sized tensile specimens were used for room temperature tensile tests [Fig. 1(d)].Results and DiscussionsDissimilar materials Ta-10W/GH3128 have uneven weld structures. The Ta-10W side structure of the weld is dominated by short dendrites and equiaxial crystals, and the GH3128 side structure is dominated by needle-like columnar crystals. Under the processing conditions of focus center welding, an island-like structure appears in the weld, consisting of a Ta-10W reaction layer washed out into the molten pool and solidified. (Figs. 3 and 4). Under the process conditions of 5500 W, 5 m/min, and 0.2 mm, the weld tissue was relatively homogeneous; the island-like tissue disappeared; and the centerline of the weld was relatively clear (Fig. 5). A reaction layer was observed on the Ta-10W side in all three joints. For 5500 W, 5 m/min, 0.2 mm process conditions, the weld displayed an asymmetric X-morphology, and there were no cracks in the weld (Fig. 2). The thickness of the reaction layer was 5 μm near the Ta-10W side, whereas the thickness of the unmelted layer was about 2 μm near the GH3128 side. In the middle of the weld, both the reaction and unmelted layers disappeared (Fig. 4). The microhardness of the joint was lowest when welding offset was 343?416 HV (Fig. 9). The highest tensile strength of 428 MPa was observed for approximately 77.8% of the Ta-10W base material tensile strength (Fig. 10). The fracture mode of the joint was a mixed ductile-dominated fracture (Fig. 11).ConclusionsThe 3 mm thick Ta-10W/GH3128 with dissimilar butt joints was obtained in the atmospheric environment with a fiber laser. The weld exhibited an asymmetric X morphology at 5500 W, 5 m/min, and 0.2 mm processing conditions. The welded microstructures were relatively uniform consisting of mainly short dendrites, equiaxial crystals, and long columnar crystals. A reaction layer with a thickness of 5 μm was formed on the Ta-10W side and disappeared in the middle of the weld. The results of tensile experiments show that the sample broke on the Ta-10W side reaction layer. The tensile strength reached 428 MPa, and the joint displayed a mixed ductile-dominated fracture mode.

ObjectiveIn power plant boilers, T91 and TP347H are generally welded using argon arc welding. Traditional argon arc welding requires beveling, a substantial wire filling amount, low welding efficiency, and high overall heat input. Excessive and uneven heat input can lead to the formation of blocky ferrite and ‘island structures’ at the weld joint, promoting component segregation and carbon migration and softening the joint structure. A large bevel angle can increase the unevenness in the thickness direction along the wall of the weld joint, which can affect the performance of dissimilar steel weld joints under high-temperature and high-pressure service conditions.MethodsThis study uses a handheld single-mode laser swing welding device with a rated power of 1500 W, swing amplitude of up to 5 mm, and swing frequency of 0?300 Hz. The filler wire used is ERNiCr-3, with a diameter of 1.2 mm. The sample is a tubular sample with dimensions of Φ57 mm×4.5 mm, without beveling, which is welded using a butt joint without preheating and subsequently air-cooled to room temperature. The area within a 10 mm range of the inner and outer walls of the welding position is cleaned before welding, removing water rust, oil stains, and other impurities to expose the metallic luster. Nitrogen is used as the shielding gas and is blown into the molten pool. The test tube is aligned with calipers and fixed with a handheld laser welder for spot welding. The tube sample is fixed and rotated using a three-jaw chuck, and single-pass full-penetration welding is performed.Results and DiscussionsThe weld seam is well formed with no evident macroscopic defects such as concavity, undercut, or surface pores. No defects are observed inside the joint, such as pores, inclusions, cracks, lack of fusion, or lack of penetration (Fig. 4). No “island structure,” “beach structure,” or delta ferrite can be found in the heat-affected zone (HAZ) of the welded joint (Fig. 6). The quantity of fine precipitates in the fine crystal region is significantly reduced, the shape of the carbides is round, and the size increases; however, some small precipitates remain [Fig. 8(b)]. The coarse crystal region has the least amount of precipitates, with only tiny precipitates observed [Fig. 8(c)]. Under the action of high energy factors, the carbides of M23C6 and MX in the coarse-grained region dissolve, the pinning effect of these precipitates disappears, and the grain boundaries begin to move. The austenite grain sizes in this region increase significantly, leading to coarsening. During rapid cooling, these coarse austenite grains transform into coarse, untempered martensite grains, forming a coarse-grained HAZ. When the overall energy input decreases gradually as the fusion line transitions to the T91 base metal, the M23C6 carbides trigger the Ostwald ripening phenomenon, manifested by a change in the shape and size of the precipitated phase becoming rounder. MX carbides contain the strong carbide-forming elements V and Nb, which can stabilize the carbides and prevent Ostwald ripening. Additionally, owing to the lower peak temperature experienced and higher cooling rate compared to the coarse-grained HAZ (CGHAZ) region, the recrystallized austenite is refined, resulting in grain sizes smaller than those in the coarse-grain region and T91 base metal. The highest hardness is observed in the HAZ, and the average tensile strength of the joints exceeds 600 MPa.ConclusionsIn this study, T91/TP347H dissimilar steel is welded with oscillating laser filling wire using a handheld single-mode laser, and the microstructure and mechanical properties of the welded joints are studied. The results show that the handheld single-mode oscillating laser can be used to weld dissimilar steel boilers with well-formed welds that are free from defects such as cracks and porosity. No δ-ferrite and island structure or beach structure caused by composition segregation is observed. Numerous precipitates appear in the TP347H side HAZ, while the T91 side HAZ exhibits a CGHAZ and fine-grained HAZ (FGHAZ) owing to the influence of the welding heat cycle. In the CGHAZ, the precipitated phase is almost completely dissolved, and M23C6 matures and coarsens. Primary austenite grains and untempered martensite are observed in the HAZ, and the highest hardness is obtained. Under the influence of laser oscillation, the weld zone presents a mixture of cellular, columnar, and equiaxed crystals, and the preferred growth direction of the columnar crystals is diversified. The average tensile strength of the joint exceeds 600 MPa. No evident cracks are observed on the surface of the specimen after bending, and the joint performance is satisfactory.